The Network Law Review is pleased to present a special issue on “Industrial Policy and Competitiveness,” prepared in collaboration with the International Center for Law & Economics (ICLE). This issue gathers leading scholars to explore a central question: What are the boundaries between competition and industrial policy?

**

Abstract: We develop a game-theoretic model to analyze optimal workplace arrangements in AI-enhanced teams where knowledge sharing is subject to location-dependent costs. Extending principal-agent theory to incorporate remote collaboration frictions, our model shows how return-to-office (RTO) policies affect incentives for employee effort and AI knowledge transfer. We identify conditions that ensure efficient in-person and remote work arrangements. Comparative statics show that higher AI adoption paradoxically reduces tolerance for remote work when it increases the frequency of costly knowledge-sharing events. Conversely, AI tools that substantially reduce collaboration costs expand the range of efficient remote or hybrid arrangements. Our results show that optimal RTO policies depend on technological capabilities and coordination frictions.

*

1. Introduction

The widespread adoption of generative artificial intelligence (AI) in the workplace is changing how employees access, apply and share knowledge, and this raises questions about optimal workplace arrangements. Although AI tools have reduced many barriers to remote collaboration, a growing body of evidence shows that tacit, complex knowledge is transferred more effectively in face-to-face settings (Yang et al., 2022; Gibbs et al., 2024). This tension has revived the debate over post-pandemic return-to-office (RTO) mandates.

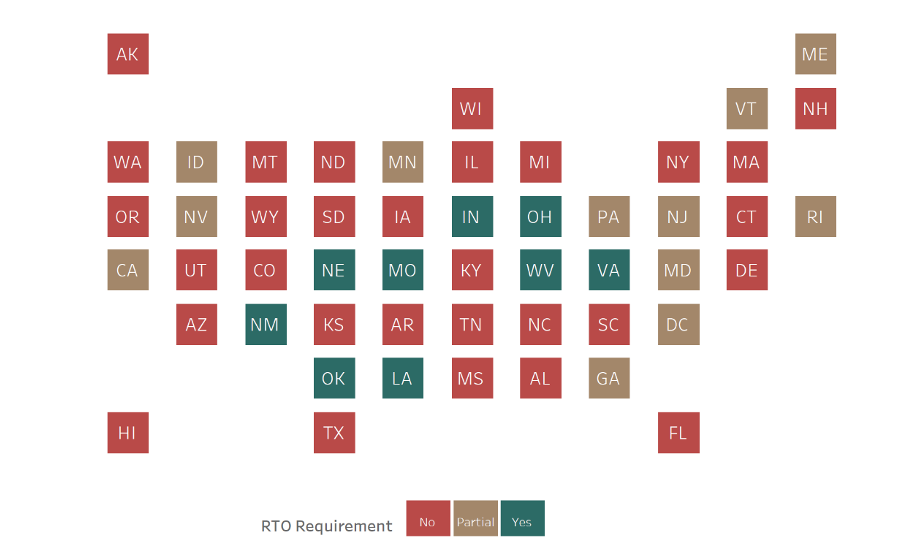

Figure 1: Return-to-Office Mandates across U.S. States and the District of Columbia (31 states have no formal RTO policy; 11 have partial mandates, and 9 require in-person work).

Figure 1 illustrates the public-sector landscape for state-government workforces as of August 2025.[1],[2] The majority of states (≈ 59%) have not issued RTO mandates, and only about 18% require full-time in-person work. This highlights substantial variation in policy responses. This variation underscores the need for a framework to evaluate optimal work arrangements and the role of AI-enabled productivity gains in shaping workplace policy.

From an industrial policy perspective, workplace arrangements serve as a strategic lever to influence economic activity and sectoral competitiveness. Knowledge-intensive industries, including technology, financial services, and professional services, require effective collaboration mechanisms that may benefit from the type of information exchange available in in-person settings, particularly when AI tools are insufficient to fully replicate face-to-face knowledge transfer (Grant, 1996).

We develop a principal-agent model that incorporates location-dependent knowledge-sharing costs into an AI-enhanced production environment. Our model extends the literature on knowledge sharing by incorporating differential costs of information transfer based on workplace arrangement— in-person versus remote work. This framework analyzes optimal compensation structures and workplace arrangements under varying technological environments, providing insights relevant for both organizational management and industrial policy.

First, we formalize how AI-enabled productivity gains interact with location-dependent knowledge sharing costs to shape optimal workplace arrangements. Second, we derive comparative statics that demonstrate that RTO policies are optimal when remote collaboration costs exceed a critical threshold, which depends on the degree of technological adoption (including but not limited to AI tools), location-specific cost savings, and the likelihood/frequency of AI knowledge acquisition. Third, we extend the analysis to hybrid arrangements, deriving the optimal remote percentage—the fraction of remote work—as a function of model parameters and highlighting how reductions in collaboration costs or cost convexity can expand the viability of remote work.

The policy implications we derive are relevant to both organizations and governments. Specifically, our model’s primitives map naturally to real-world policy contexts: remote collaboration costs and cost convexity may reflect tooling and organizational design choices (e.g., IT investment and meeting norms); location-specific savings can capture commuting, real-estate, and retention considerations shaped by public infrastructure and tax policies; and the frequency of knowledge acquisition may correspond to sectoral innovation intensity and workforce upskilling programs. Our results show that the choice between remote, in-person, and hybrid arrangements depends not only on AI productivity gains but also on how effectively AI tools reduce the costs of knowledge sharing and coordination. When AI adoption increases the frequency of knowledge sharing events, but cost frictions remain high, RTO policies improve efficiency. Conversely, when AI tools substantially reduce collaboration costs or flatten cost convexity, hybrid arrangements with higher remote shares are efficient. These findings provide a framework for designing workplace policies that adapt to technological capabilities and the nature of the work (e.g., its knowledge dependence and task-coordination needs), avoiding one-size-fits-all mandates.

2. Related Literature

Our work builds on several strands of literature in organizational economics, workplace design, and the economics of AI. Holmström (1982) provides the foundational model of moral hazard in teams and free-riding, while Alchian and Demsetz (1972) present the classic analysis of team production and monitoring. Holmström and Milgrom (1991) examine multitask principal-agent settings, with implications for incentive design when agents engage in multiple activities. Winter (2004) analyzes optimal compensation schemes for joint projects with unobservable effort, while Chakravarti et al. (2015) study mechanisms to encourage information exchange in principal-agent settings. In our model, knowledge sharing occurs within technologically-independent tasks, but incurs location-dependent costs that vary with workplace arrangements.

A related literature examines the role of coordination costs in shaping the division of labor and knowledge flows within organizations. Garicano (2000) models knowledge transfer within hierarchical organizations, and Dessein (2002) studies how communication frictions affect the allocation of decision rights. Becker and Murphy (1992) study how specialization increases coordination needs, and Aghion and Tirole (1997) characterize the trade-off between formal and real authority when information is dispersed, implying that in remote-work settings, physical distance may raise coordination costs and shift effective authority toward those with local information. Kandel and Lazear (1992) highlight the role of peer pressure in sustaining effort and cooperation in teams. These studies ground our modeling of location-dependent knowledge sharing costs and their interaction with workplace arrangements.

The literature on AI and productivity provides empirical grounding for our calibration of AI-enhanced success rates. Brynjolfsson et al. (2025) document a 15% average productivity gain from generative AI tools among customer service agents, with larger effects for less experienced workers; while estimated in customer support, effects may vary across industries, occupations, tasks, and over time. We use these estimates to parameterize the model and illustrate our findings.

Beyond Brynjolfsson et al. (2025), complementary field and experimental studies provide further support for mapping AI-induced productivity gains to higher task success probabilities. For example, in a randomized experiment, Noy and Zhang (2023) find that access to generative AI tools improves writing quality and reduces completion time among professional workers, whereas Peng et al. (2023) find that AI-assisted programming tools significantly increase code quality and development speed in a controlled setting.[3]

A growing empirical literature studies the impact of remote work on collaboration and knowledge transfer. Yang et al. (2022) find that pandemic-induced remote work at Microsoft led to more siloed communication networks, while Barrero et al. (2023) document mixed effects of remote work on innovation outcomes. These studies, largely pre-dating widespread generative AI adoption, show that remote arrangements entail coordination costs that reduce overall productivity—consistent with our model’s remote knowledge sharing cost and convexity parameter. Our results show that unless AI significantly lowers these costs, a higher probability of AI knowledge creation paradoxically strengthens the case for return-to-office arrangements.

The emerging workplace AI literature underscores the transformative potential of large language models. Eloundou et al. (2023) estimate that approximately 80% of U.S. workers could have at least 10% of their tasks affected by such models, suggesting broad potential for AI to reduce location-dependent frictions. Our results refine this view: while AI can reduce costs or flatten their curve, the optimal fraction of remote work still depends on the magnitude of these reductions relative to the cost of knowledge transfer and the likelihood of new knowledge-sharing events.

Our contribution to this literature provides a formal model that jointly incorporates AI-enhanced productivity and location-dependent knowledge sharing costs. We derive a threshold that determines when remote versus in-person work is optimal, and characterize the optimal fraction of remote work as a function of the attributes of a given work environment. This framework offers policy implications for RTO arrangements in AI-augmented organizations. This analysis builds on our work in Durango-Cohen et al. (2025), which develops a theoretical framework for knowledge sharing and incentive design. Here, we apply the framework to specifically examine RTO policies under location-dependent collaboration costs.

3. Model

We analyze a workplace setting with an employer E and two agents i ∈ {1,2}, whose tasks are technologically independent but jointly determine project success: the project succeeds only if both tasks succeed. Each agent chooses whether to exert costly effort ei ∈ {0,1} on their assigned task. Exerting effort ei = 1 raises the probability of task success from γ to β, at cost c > 0, where 0 < γ < β < 1.

A key feature of the model is the possibility of AI-enhanced knowledge acquisition. With probability ρ, one agent obtains AI-generated knowledge that, if the agent exerts effort, increases her task success probability from β to α, where β < α < 1. The knowledge-holding agent may choose to share this knowledge with her colleague or retain it privately. If shared, the knowledge increases both agents’ task success probabilities from β to α.

We incorporate location-dependent costs of knowledge sharing. When agents work in-person, sharing knowledge incurs no additional cost,[4] cr = 0. When agents work remotely, sharing knowledge incurs cost cr > 0, reflecting technological and coordination frictions associated with remote collaboration. Remote work also provides a baseline flexibility benefit ∆ > 0 to agents,[5] which in a competitive labor market translates into lower required compensation. We assume a competitive labor market, which means this enables the employer to appropriate ∆ as a cost saving (Bloom et al., 2015).[6] In addition, remote work yields a direct cost saving K ≥ 0 for the employer from reduced overhead expenses. Relative to in-person work, a remote arrangement therefore increases the employer’s bottom line by K + ∆.

This setup captures the key policy question: As new tools (for example, those tailored by employees to streamline specialized workplace efforts) enhance the likelihood of tasks being completed successfully, possibly even reducing the cost of sharing new knowledge in remote settings, what are the implications for optimal workplace arrangements and compensation design?

The game proceeds as follows. In the first stage, the employer announces the compensation contract Cim = (,P) and the workplace arrangement m ∈ {0,1}, with m = 0 denoting in-person work and m = 1 denoting remote work. Next, with probability ρ, one agent acquires AI knowledge and decides whether to share it. Both agents then simultaneously choose effort levels ei ∈ {0,1}. Finally, the overall project outcome is observed and payments are made according to the agents’ contracts.[7] Individual agent efforts and/or task outcomes may or may not be observable.[8]

4. Results

We analyze the model under different information and workplace regimes (observable versus unobservable effort) and workplace arrangements (in-person, remote, and hybrid). As a preview, optimal compensation and workplace policies depend critically on the magnitude of remote knowledge sharing costs and benefits relative to the productivity gains from knowledge sharing. In the following, we characterize the optimal contracts, cost thresholds, and workplace shares under each regime.

4.1. Observable Effort Benchmark

When everything is observable, the employer can directly condition wages on the agents’ actions.[9] This enables the employer to readily achieve the ideal outcome, where both agents exert effort and any acquired knowledge is shared between them. In this benchmark, whether agents are working in-person or remotely only affects the employer’s profit through the agents’ cost of knowledge sharing and remote work benefits.

Lemma 1 (Observable actions). Suppose agents’ effort, knowledge, and knowledge sharing are observable and contractible (see here).

Under this benchmark, only location-dependent costs and benefits matter in determining the employer’s choice of workplace arrangement, as moral hazard is not a factor.

4.2. Unobservable Effort, Observable Task Outcomes

More realistically, when neither agents’ efforts, knowledge possession, nor knowledge sharing are observable, the employer cannot enforce actions directly. Instead, compensation must be linked to observable outcomes—individual task success (si = 1) and joint project success (si = sj = 1).[11] This creates two problems for the principal: first, incentivizing costly effort by the agents, and second, incentivizing a new knowledge holder, should one exist, to share their knowledge. Knowledge sharing is frictionless when work is in person (cr = 0) but incurs a cost cr > 0 when work is remote.

Lemma 2. The employer offers contracts comprising task success wages wi and project success bonus P (see here).[12]

In this benchmark, ![]() minimizes the principal’s cost of incentivizing effort by the agents. In-person work involves no extra payment to induce knowledge sharing, while remote work requires offering project success pay, P. An increase in the friction of sharing knowledge remotely in turn increases the total compensation agents receive proportionally. This makes remote work less profitable to the principal unless the benefits of remote work, K + ∆, offset the additional compensation cost.

minimizes the principal’s cost of incentivizing effort by the agents. In-person work involves no extra payment to induce knowledge sharing, while remote work requires offering project success pay, P. An increase in the friction of sharing knowledge remotely in turn increases the total compensation agents receive proportionally. This makes remote work less profitable to the principal unless the benefits of remote work, K + ∆, offset the additional compensation cost.

Intuitively, it follows that in environments where new knowledge is generated rapidly, all else held equal, remote work is less likely to be profitable to the principal, and return-to-office policies are more likely to be efficient.

In particular, the model gives a clear condition for the employer’s choice of workplace as a function of the cost of remote knowledge sharing, cr.

Proposition 1. There exists a cost threshold such that in-person work, see here.

Corollary 1. When AI tools do not reduce the cost of sharing new knowledge remotely, RTO policies can enhance efficiency.

These comparative statics offer simple intuition. The threshold for remote work being optimal decreases in the probability of an agent acquiring new knowledge that enhances efficiency, since a higher likelihood of new knowledge entails a higher likelihood of costly remote knowledge sharing.[13] Consequently, in-person work and RTO policies become more attractive in such environments. By contrast, the threshold increases in the remote-specific benefits (K + ∆) and the productivity gain from the new knowledge (α − β), both of which raise the employer’s tolerance for remote work.

4.3. Hybrid Workplace Arrangements

We now allow the employer to choose a hybrid workplace policy, with m ∈ [0,1] denoting the fraction of work conducted remotely, such that m = 0 and m = 1 correspond to fully in-person and fully remote work, respectively.

We assume that the cost of sharing knowledge increases convexly in the fraction of remote work, such that cr(m) = cr ·[(1+m)η−1], where η > 1. The convexity assumption captures the idea that a small number of remote days can be coordinated at low cost, while marginal coordination costs rise quickly at higher remote shares as opportunities for more seamless knowledge transfer decline.[14]

Sharing incentive under hybrid. With contract Cim = siwi+sisjP(m), the informed agent’s nonwage payoff from keeping their new knowledge private is αβ P(m), while sharing yields α2 P(m) − cr(1 + m)η. The incentive compatibility condition for sharing, which gives P(m) at equality, is:

![]()

Substituting P(m) into the employer’s objective yields the principal’s profit, Πunobshb(m).

Proposition 2. Let m ∈ [0,1] denote the fraction of remote work. The employer’s profit under hybrid work is: see here.

Corollary 2. When AI technologies increase the likelihood of new operational knowledge, RTO policies can enhance efficiency.

It follows from Proposition 2 that a reduction in the cost of sharing new knowledge while working remotely, cr, unambiguously increases the optimal remote share of remote work, m∗.[15] On the other hand, an increase in the likelihood of new knowledge, ρ, decreases the optimal fraction of remote work. This pattern is consistent with Proposition 1, only it manifests in the optimal fraction of remote work instead of a threshold for an all-or-nothing remote work decision by the principal. At the extremes, m∗ → 0 when remote savings fail to offset coordination costs, and m∗ → 1 when remote knowledge sharing frictions vanish.

Tools for more effective knowledge sharing in remote settings can increase the optimal fraction of remote work in two ways: (i) lowering the baseline level cr through, e.g., faster information retrieval, automated knowledge transfer, and asynchronous communication support; and (ii) reducing the cost convexity of remote work frictions by mitigating the steep increase in marginal frictions at higher remote shares (e.g., with automated coordination of in-person days). Both effects can make hybrid arrangements with greater remote shares more desirable.[16]The paradox here is that AI technologies, which have the potential to introduce enormous efficiencies, at the same time can make remote work less efficient—unless they also reduce the knowledge sharing frictions associated with remote work. In practice, the magnitude of this effect may further vary by team size, its complexity, as well as the modularity of knowledge and/or expertise within the focal team, and other teams with which the focal team interfaces.

5. Simulations

The theoretical results in Propositions 1 and 2 characterize thresholds for remote coordination costs and optimal hybrid workplace shares as functions of key model parameters. To assess the practical relevance of these thresholds, we calibrate the model using empirically-grounded values.[17]

We calibrate the baseline task success probability without new knowledge (β) and new-knowledge-enhanced success probability (α) using Brynjolfsson et al. (2025). In their large-scale field experiment with customer-service agents, the control and treatment groups, prior to a new AI deployment, both achieved a first-call resolution rate of approximately 0.82, which we take as the representative baseline β. Following AI deployment, the treatment group’s productivity increased by roughly 15% on average. Applying this gain to the baseline success rate yields α = 0.82 × 1.15 ≈ 0.94.[18]

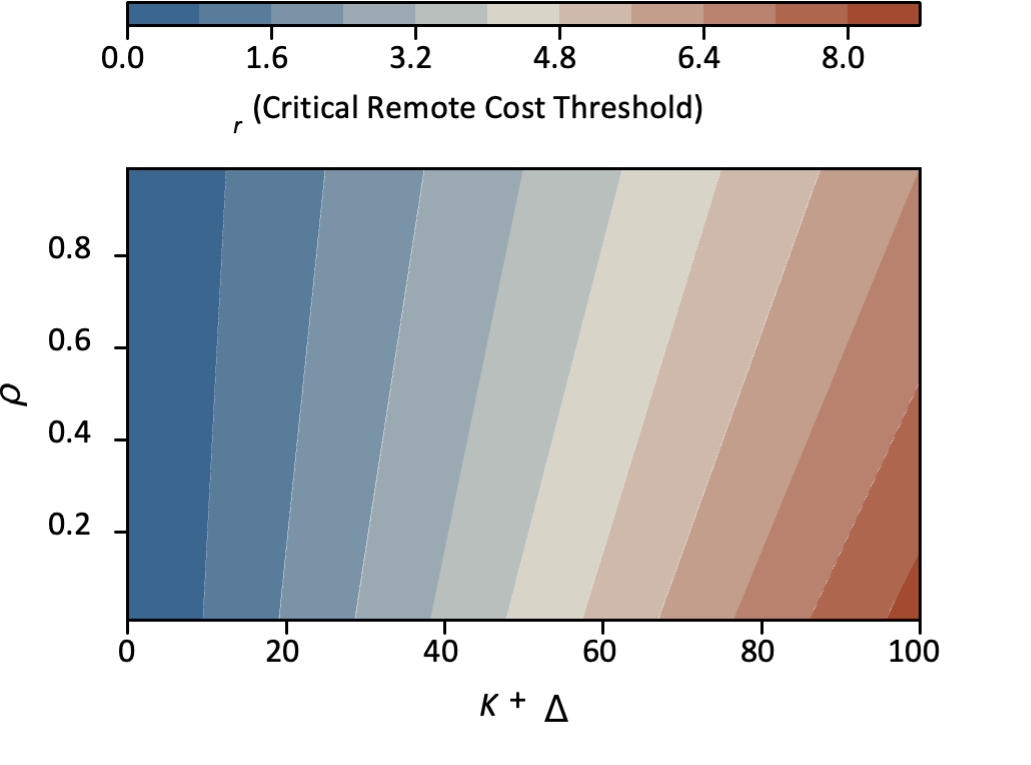

Figure 2: Remote knowledge sharing cost threshold,, as a function of remote work benefits, K+∆, and new knowledge likelihood, ρ.

Figure 2 demonstrates that the remote cost threshold increases with the benefits from remote work, (K + ∆), and decreases with the probability of new AI knowledge acquisition, ρ. Higher remote benefits expand the range of coordination costs in which remote work is viable, while a higher likelihood of new knowledge narrows this range by increasing the frequency of costly knowledge-sharing events. These results highlight that AI adoption, absent cost mitigation of remote knowledge sharing frictions, paradoxically strengthens the case for return-to-office policies.

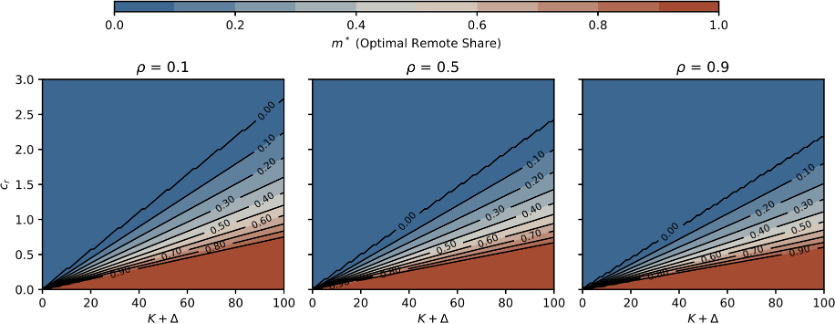

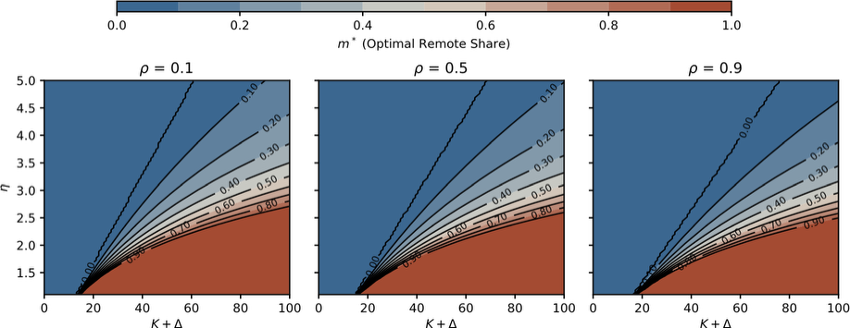

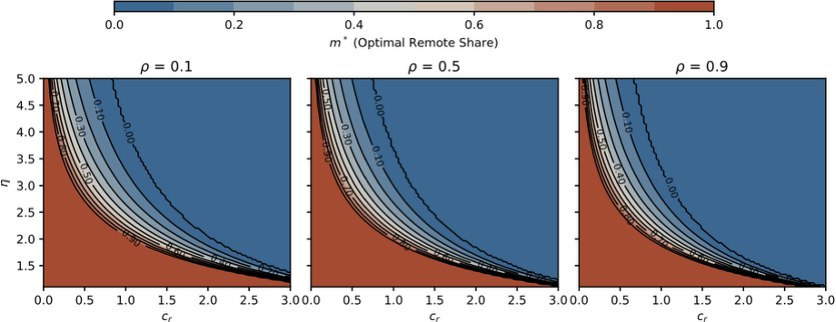

Figures 3–5 present the optimal fraction of remote work, m∗, under different combinations of remote benefits, K + ∆, baseline coordination cost, cr, and remote sharing cost convexity, η, across three values of the new knowledge likelihood, ρ.

Figure 3: Optimal fraction of remote work, m∗, as a function of remote benefits, K +∆, and remote knowledge sharing cost, cr, for different new knowledge likelihoods, ρ (with the convexity parameter η = 3).

Figure 3 plots the optimal fraction of remote work, m∗, as a function of benefits of remote work, K + ∆ (horizontal axis), and cost of sharing knowledge remotely, cr (vertical axis). For all values of the likelihood of new knowledge, ρ, higher benefits lead to a higher optimal remote work share, m∗, with the effect most pronounced when the baseline remote knowledge sharing cost, cr, is low. As cr increases, the optimal fraction of remote work declines sharply, particularly when the likelihood of new knowledge, ρ, is high. When ρ = 0.9, the high-m∗ region, where remote work is favored, is concentrated at relatively low costs of sharing knowledge remotely, cr; even moderate cr costs significantly reduce the feasibility of remote work altogether, reflecting the conflict between AI leading to new knowledge events and remote knowledge sharing costs lagging behind. By contrast, in the low-ρ panel (ρ = 0.1), the high-m∗ region extends much further up along the cr axis, indicating that remote work remains viable over a wider range of coordination costs.

Figure 4 plots the optimal fraction of remote work, m∗, as a function of the remote work benefits, K + ∆ (horizontal axis), and remote knowledge sharing cost convexity, η (vertical axis). Lower values of η (flatter cost curves) support higher shares of remote work when the benefits from remote work are large.

Figure 4: Optimal fraction of remote work, m∗, as a function of the benefits of remote work, K +∆, and remote knowledge sharing cost convexity, η, at different new knowledge likelihoods, ρ (with the base cost of remote knowledge sharing cr = 1).

As η increases, the optimal remote share drops rapidly, particularly for higher values of benefits from remote work. This effect is stronger at higher likelihoods of new knowledge, ρ, again highlighting that a high pace of new knowledge events associated with AI concurrently make remote work increasingly inefficient and return-to-office policies optimal.

Figure 5: Optimal fraction of remote work, m∗, as a function of remote knowledge sharing cost, cr, and remote cost convexity, η, at different new knowledge likelihoods, ρ (with the benefits from remote work K + ∆ = 50).

Figure 5 plots the optimal fraction of remote work, m∗, as a function of the base cost of remote knowledge sharing, cr (horizontal axis), and the remote cost convexity parameter, η (vertical axis), holding the benefits from remote work, K+∆, fixed. Both higher cr and higher η reduce the optimal fraction of remote work, with the combination of high cr and high η sharply limiting the parameter space where remote work is efficient. Given a low range on the likelihood of new knowledge, ρ, some remote work remains optimal under moderate costs; at high ρ, the feasible region for remote work efficiency shrinks dramatically, with high m∗ only sustainable when both cr and η are low.

Taken together, the figures demonstrate that higher remote work benefits, K + ∆, expand the feasible range for remote work being efficient, but only when the frictions of remote knowledge sharing, as given by cr and η, remain relatively low or moderate. Higher likelihoods of new knowledge, ρ, without corresponding reductions in remote sharing costs, cr or η, tighten these constraints in support of stricter RTO policies and reinforcing the need for AI tools, new processes, codification strategies, or management approaches that directly lower remote coordination costs to justify and sustain hybrid and remote work arrangements.

6. Conclusion

We identified wide disparities in return-to-office (RTO) policies across U.S. states. We then developed a theoretical framework for evaluating the efficiency of RTO policies in an economy augmented by a constant flow of new knowledge, in light of the undergoing AI revolution. Our analysis identifies a threshold on the cost of remote knowledge sharing, above which in-person work can be optimal. The threshold decreases in the likelihood of new AI knowledge being generated, because more frequent knowledge creation increases the frequency of costly remote knowledge sharing events. We extend the analysis to hybrid-workplace situations and find analogous results. Our calibrated simulations lend some justification for RTO policies.

Our results entail that, somewhat paradoxically, AI technologies, which have the potential to introduce various efficiencies, at the same time can make remote work less efficient—unless some of their efficiencies themselves reduce the knowledge sharing frictions associated with remote work.

That is, from a policy perspective, AI adoption alone does not automatically support broader remote work arrangements. Unless AI substantially reduces remote knowledge sharing and coordination frictions, environments characterized by high likelihoods of new knowledge generation strengthen the case for strict RTO policies. Conversely, improvements in digital infrastructure or workplace processes that lower remote knowledge sharing frictions shift the optimal arrangement toward some hybrid arrangements.

These findings and their calibrated simulations provide some justification to policies that require RTO or pursue “anchor day” strategies, which reserve coordination-intensive work for in-person days.

Overall, workplace policy design should be contingent on organization- and work unit-specific attributes. Given a workplace environment where the occurrence of new knowledge generation is high, as may be the current case with generative AI, stricter RTO policies are more likely to be efficiency enhancing. Moreover, managers should plan to time the rollouts of AI technologies alongside process designs and corresponding infrastructure upgrades to support remote knowledge sharing and coordination.

Elizabeth J. Durango-Cohen*, Yidan Sun** and Liad Wagman***

*Illinois Institute of Technology, **Binghamton University, ***Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

Citation: Elizabeth J. Durango-Cohen, Yidan Sun and Liad Wagman,Return-to-Office Policies and AI Knowledge Sharing: A Game-Theoretic Analysis, Industrial Policy and Competitiveness (ed. Thibault Schrepel & Dirk Auer), Network Law Review, Fall 2025.

References:

- Aghion, P. and J. Tirole (1997): “Formal and real authority in organizations,” Journal of political economy, 105, 1–29.

- Alchian, A. A. and H. Demsetz (1972): “Production, information costs, and economic organization,” The American economic review, 62, 777–795.

- Baker, G., R. Gibbons, and K. J. Murphy (2002): “Relational Contracts and the Theory of the Firm,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117, 39–84.

- Barrero, J. M., N. Bloom, and S. J. Davis (2023): “The evolution of work from home,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 37, 23–49.

- Becker, G. S. and K. M. Murphy (1992): “The division of labor, coordination costs, and knowledge,” The Quarterly journal of economics, 107, 1137–1160.

- Bloom, N., J. Liang, J. Roberts, and Z. J. Ying (2015): “Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130, 165–218.

- Brynjolfsson, E., D. Li, and L. Raymond (2025): “Generative AI at work,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 140, 889–942.

- Chakravarti, A., C. He, and L. Wagman (2015): “Inducing knowledge sharing in teams through cost-efficient compensation schemes,” Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 13, 71–90.

- Dessein, W. (2002): “Authority and communication in organizations,” The Review of Economic Studies, 69, 811–838.

- Durango-Cohen, E., Y. Sun, and L. Wagman (2025): “AI Knowledge Sharing: Thresholds, Incentives, and Strategic Implications,” Working Paper.

- Eloundou, T., S. Manning, P. Mishkin, and D. Rock (2023): “GPTs are GPTs: An early look at the labor market impact potential of large language models,” arXiv preprint:2303.10130.

- Garicano, L. (2000): “Hierarchies and the Organization of Knowledge in Production,” Journal of political economy, 108, 874–904.

- Gibbs, M., F. Mengel, and C. Siemroth (2024): “Employee innovation during office work, work from home and hybrid work,” Scientific Reports, 14, 17117.

- Grant, R. M. (1996): “Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm,” Strategic Management Journal, 17, 109–122.

- Holmström, B. (1982): “Moral hazard in teams,” The Bell Journal of Economics, 324–340.

- Holmström, B. and P. Milgrom¨ (1991): “Multitask principal–agent analyses: Incentive contracts, asset ownership, and job design,” The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 7, 24–52.

- Kandel, E. and E. P. Lazear (1992): “Peer pressure and partnerships,” Journal of political Economy, 100, 801–817.

- Noy, S. and W. Zhang (2023): “Experimental evidence on the productivity effects of generative artificial intelligence,” Science, 381, 187–192.

- Peng, S., E. Kalliamvakou, P. Cihon, and M. Demirer (2023): “The impact of ai on developer productivity: Evidence from github copilot,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.06590.

- Prendergast, C. (1999): “The provision of incentives in firms,” Journal of economic literature, 37, 7–63.

- Winter, E. (2004): “Incentives and discrimination,” American Economic Review, 94, 764–773.

- Yang, L., D. Holtz, S. Jaffe, S. Suri, S. Sinha, J. Weston, C. Joyce, N. Shah, K. Sherman, B. Hecht, et al. (2022): “The effects of remote work on collaboration among information workers,” Nature Human Behaviour, 6, 43–54.

Citations:

- [1] Source: Authors’ compilation from publicly available state RTO directives as of August 8, 2025. State-by-state table and corresponding links are provided in Appendix D.

- [2] Although these rules apply only to state employees, they signal broader regional preferences and can influence private-sector practices through spillover norms, contracting requirements, and local labor-market expectations.

- [3] For broader perspectives, Prendergast (1999) surveys the provision of incentives in firms, and Baker et al. (2002) develop a theory of relational contracts, including in settings where it is difficult to contract on specific actions.

- [4] For simplicity we set the in-person cost of knowledge sharing to zero. Results continue to hold if c_onsite ≥ 0, in which case cr is interpreted as the incremental cost of knowledge sharing in remote relative to in-person settings , i.e., replace cr with ∆c = cr – c_onsite.

- [5] If workers capture a share θ ∈ [0,1] of ∆, where θ is the percentage retained by workers and (1−θ) is captured by the employer, we would replace K + ∆ with K + (1 − θ)∆ at no qualitative loss.

- [6] In our construction, the participation constraint binds at zero expected utility, given limited liability and competitive labor markets.

- [7] For tractability, we assume identical agents and jobs (i.e., c, β, and ρ are common across all agents/tasks). The framework readily extends to heterogeneous cases: differences in c, β, or ρ simply yield heterogeneous P functions and thus job- or agent-specific remote share values.

- [8] In Section 4.1, individual effort levels are observable; in Section 4.2, efforts are not observable but task outcomes are; and in Appendix C, only the overall project success is observable.

- [9] In this benchmark, effort ei, knowledge status, and knowledge-sharing decisions are observable and contractible. The employer can condition wages directly on both effort and sharing.

- [10] For tie-breaking, an arbitrarily small ε > 0 is implicitly added to the relevant wage to ensure a unique equilibrium.

- [11] In this setting, effort ei is unobservable, whereas individual task outcomes and project success are observable. If new knowledge exists, sharing can be induced through a project success bonus P.

- [12] Here, P denotes the project success bonus, awarded to both agents upon successful completion of both tasks.

- [13] To be clear, these comparative statics should be interpreted under the assumption that AI adoption increases the frequency of tacit knowledge events; other channels, such as workflow codification, would instead operate through cr and/or η.

- [14] The convexity parameter η captures how sharply coordination costs rise as remote work increases: lower values of η (just above 1) indicate that costs rise gradually, allowing more remote days before significant frictions occur; higher values of η imply that costs escalate rapidly, meaning even a modest increase in remote days can sharply increase coordination difficulties. This pattern is consistent with observed hybrid policies and the literature, where one to two remote days may impose minimal frictions, but higher amounts create more pronounced coordination challenges.

- [15] The effect of lower η, i.e., of flattening the cost convexity parameter for remote knowledge sharing, are similar to a decrease in cr, provided the benefits of remote work, K + ∆, are non-negligible.

- [16] In Appendix C, we show that these results extend to a setting where the principal can only observe the overall project outcome can be observed.

- [17] In Figures 2–5, K + ∆ is plotted on the 0–100 range, cr on the 0–3, and η on the 0–5 range. Values are chosen for illustrative purposes.

- [18] Here, the 15% improvement refers to task success probability (not just productivity); this mapping is an approximation, and the qualitative results do not depend on this exact value.

- [19] The employer can contract on knowledge status and sharing decisions. The wage mcr is paid only if the knowledge-holding agent shares, covering the sharing cost cr.

- [20] Because β − γ is the smallest marginal increase in success probability from exerting effort (occurring when no knowledge is present), setting ensures the effort incentive compatibility constraint holds in all knowledge states, regardless of whether knowledge arrives.