The Network Law Review is pleased to present a special issue on “Industrial Policy and Competitiveness,” prepared in collaboration with the International Center for Law & Economics (ICLE). This issue gathers leading scholars to explore a central question: What are the boundaries between competition and industrial policy?

**

Abstract: The European Union’s recent wave of digital regulations, especially the Digital Services Act (DSA), highlights a strategic use of law as an instrument of industrial policy and global digital influence. While China has explicitly cultivated national technology champions through state-led industrial policy, the United States has largely relied on market-driven innovation and occasional strategic interventions in areas of national interest such as AI and semiconductor supply chains. In contrast, the EU has pursued regulatory leadership to assert “digital sovereignty” and shape international standards. This paper argues that the DSA functions not only as a legal framework for safer online spaces but also as a lever of industrial strategy and competitiveness.

Building on Schumpeter’s notion of creative destruction and Aghion’s work on competition and innovation, we examine how the DSA’s regulatory approach may simultaneously support complementary innovation (for example, in compliance and risk-assessment tools) while constraining more radical product innovation through heightened procedural and liability requirements. In this sense, the DSA becomes a case study in how industrial policy and innovation dynamics interact within a regulated digital economy.

The paper shows how the Brussels Effect – the EU’s ability to export its rules globally – is amplified by the DSA, incentivizing global platforms to adopt European norms in content moderation and platform design. We discuss the strategic incentives driving harmonization of platform practices (liability risks, cost-efficiency, scale of moderation) and the resulting implications for innovation, market access, and long-term competitiveness.

*

1. Introduction

The European Union’s recent wave of digital regulations, especially the Digital Services Act (DSA),[1] highlights a strategic use of law as an instrument of industrial policy and global digital influence.[2] While the United States and China have focused on cultivating technological champions and market dominance, the EU has pursued regulatory leadership to assert “digital sovereignty” and shape international standards.[3] This paper argues that the DSA functions not only as a legal framework for safer online spaces but also as a lever of industrial strategy and competitiveness. Although the DSA’s long-term effects on markets and innovation are still unfolding, its design and early implementation already position it as a key mechanism through which the EU projects its industrial ambitions and global regulatory behavior.[4]

While the DSA exemplifies Europe’s ambition to project regulatory power globally, it also raises a forward-looking question: how will such a sovereignty-driven framework influence innovation dynamism within the EU itself? Understanding whether the DSA enables or constrains innovation will be central to assessing its long-term policy impact.

Yet, beyond questions of sovereignty and competitiveness, regulation itself can influence innovation trajectories. Classic work in innovation economics shows that institutional frameworks shape the direction and intensity of inventive effort and through that raising the question of how the DSA may affect innovation dynamism within the EU. Regulation does not merely enforce compliance; it can also channel the direction of innovation. As Arrow[5], Nelson, and Winter[6] demonstrated, institutional environments and rule-making structures influence, especially under uncertainty, where inventive effort is concentrated, which economically feasible routines persist, and which are abandoned. In this sense, Schumpeter’s notion of creative destruction offers a useful lens: capitalist innovation is not a steady process of improvement, but an evolutionary one driven by the ‘perennial gale’ of technological and organizational change that incessantly “revolutionizes the economic structure from within, destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one.”[7] This raises a broader question: to what extent does the DSA foster innovation dynamism within Europe, or risk constraining it through heightened proceduralization?

A core process governed under the DSA is content moderation. Content moderation balances freedom of speech rights and provides legal reasons for moderation decisions, divided in legal reasons (e.g., national criminal law) or contractual reasons (Terms of Service).

This distinction between legal and contractual grounds also resonates with recent U.S. regulatory debates. There, antitrust and consumer protection enforcement, particularly through the FTC, has increasingly looked to Terms of Service (ToS) as an entry point for intervention, emphasizing transparency and accountability in how platforms enforce their own rules.[8] Such approaches reflect a shared regulatory aspiration: to discipline platform power not only through substantive law but also through the governance of contractual standards.[9]

ToS are standard contracts that platforms conclude with their users when signing up for the platforms or services. The ToS automatically implement the platform’s Community Standards in the contract between the user and the platform to define what is allowed or restricted on the platform. For example, a platform could have a clause in its Community Standards that could sanction the posting of unicorn content as part of its right to contractual freedom. The dominance of ToS-based governance also has implications for innovation. From a complexity perspective,[10] self-regulatory systems operating at scale can develop adaptive path dependencies: the rules and enforcement architectures they embed shape the evolution of future technologies (moderation tools and organizational routines).[11] As Kauffman observed, complex adaptive systems evolve at the “edge of chaos,”[12] where internal order and external adaptation co-produce new forms of stability. In such systems, selection acts not only on outcomes but also on the architectures that constrain future adaptation, a dynamic equally relevant to institutional self-regulation or to fringe cases of violation/non-violation of platform rules and the potential virality of such content.[13]

When faced with strict EU rules that carry hefty penalties,[14] major tech firms often implement the required changes globally rather than maintain separate regimes, effectively exporting EU norms abroad.[15] The EU explicitly leverages its single market, 450 million consumers, as geopolitical and economic leverage to project its regulatory preferences worldwide.[16]

Regulation is often seen as a constraint on industry, but in the European Union’s digital strategy, it also serves an enabling, market-shaping role, e.g. through the creation of safer spaces.[17] Here, “market-shaping” refers to the EU’s use of regulation not merely to restrict harmful conduct but to structure incentives, coordinate expectations, and open new domains for competition and innovation. As the United States and China secure competitive advantage through the creation of technology, whether consumer platforms, advanced AI, or national champions, the EU is asserting its advantage in the creation of rules for the digital economy.[18]

This paper examines the DSA’s dual role as a legal framework for online safety and as a de facto instrument of industry shaping policy. We analyze empirical trends from the DSA’s Transparency Database to illustrate enforcement patterns and platform adaptations and discuss why platforms are incentivized to favor global Community Standards over fragmented national laws. This reliance on ToS-based enforcement also complicates empirical assessment: if platforms categorize most removals as contractual rather than legal violations, the resulting transparency data may underrepresent the scale of illegal content and give regulators a distorted picture of compliance under the DSA, posing the risk to marginalizing platform’s problems with legally relevant violations.

2. Empirical Trends in DSA Enforcement: Insights from the SoR Transparency Database

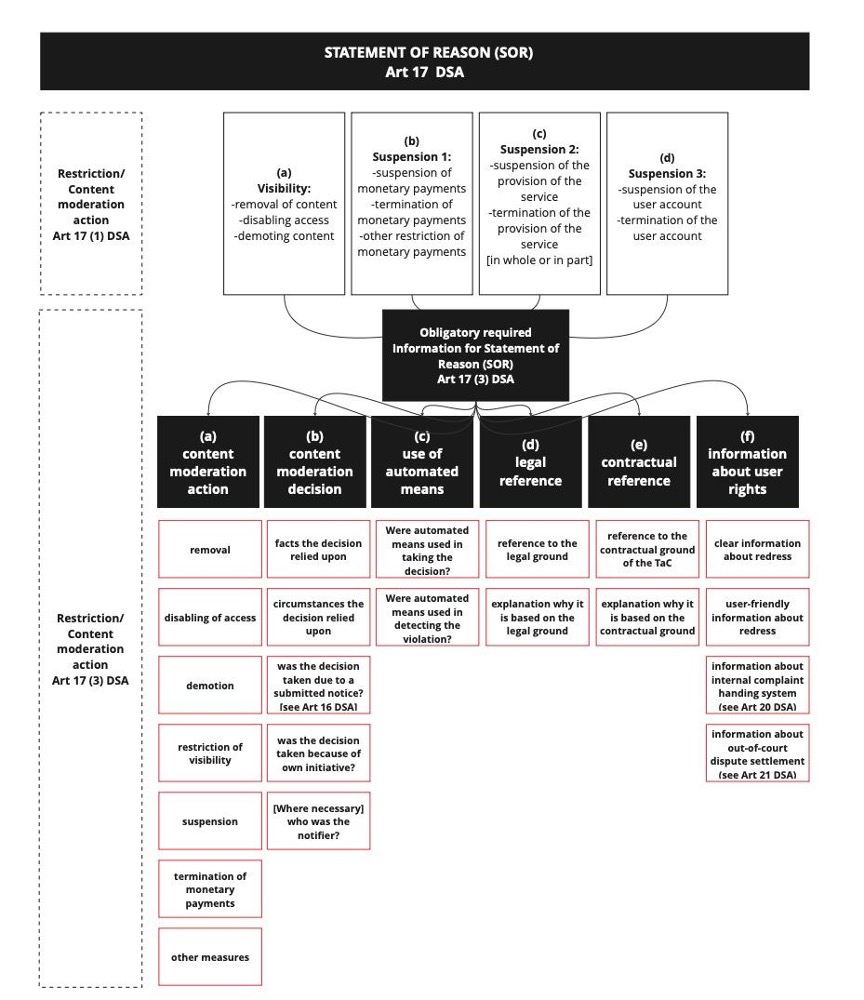

A unique feature of the DSA is its emphasis on transparency in platform enforcement actions.[19] The EU provides a Transparency Database and dashboard for these SoRs, offering a first empirical glimpse into how platforms are implementing the DSA and adjusting their practices. [20] Figure 1 provides an overview of what Article 17 demands from online platforms as information in their Statement of Reasons (SoR) entries, for example, the norm that the platform based the moderation decision on according to Art 17 (3) (d) for legal grounds and (e) for contractual references like the Terms of Service (ToS). The data was collected on the 13th of August 2025 and shows entries in the database from the 25th of September 2023 to the date of data collection.

This asymmetry between contractual and legal enforcement also raises questions about how platforms innovate under regulatory pressure. Rather than investing in differentiated legal compliance systems across jurisdictions, companies may be innovating around compliance, embedding their Community Standards into technical architectures and moderation workflows as default rules. This reflects how institutional frameworks condition innovation incentives. As Galasso and Schankerman show in their study of patent rights, legal institutions can shape not only the rate but also the direction of inventive effort and through that encourage adaptive, incremental innovation within existing constraints rather than more radical structural change. [21]

Figure 1: Overview Statement of Reasons (SOR) legal overview and process/action structure

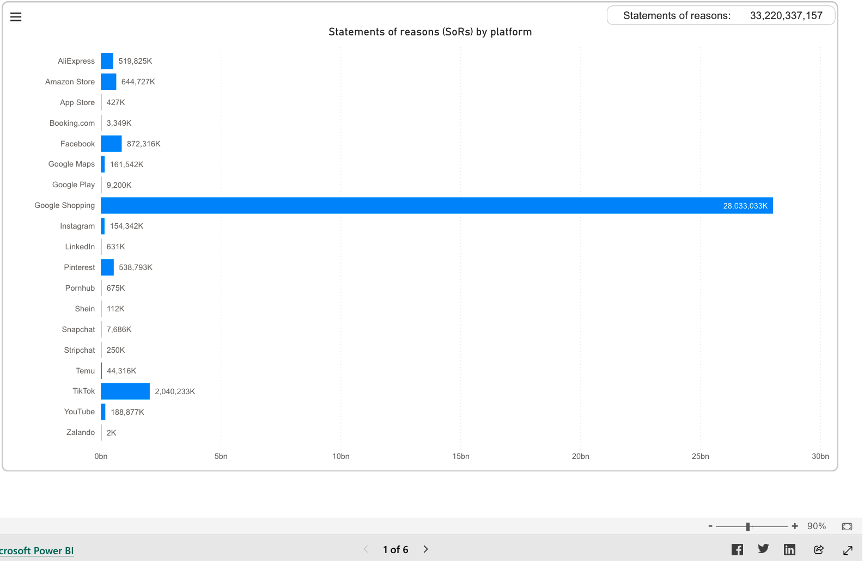

Figure 2: Volume of “Statements of Reasons” for Terms of Service violations issued by Very Large Online Platforms and Very Large Search Engines

As illustrated above, the volume of content removals (with accompanying SoRs) varies widely across platforms, and so does their enforcement preference between Terms of Service (ToS) and legal removal grounds.

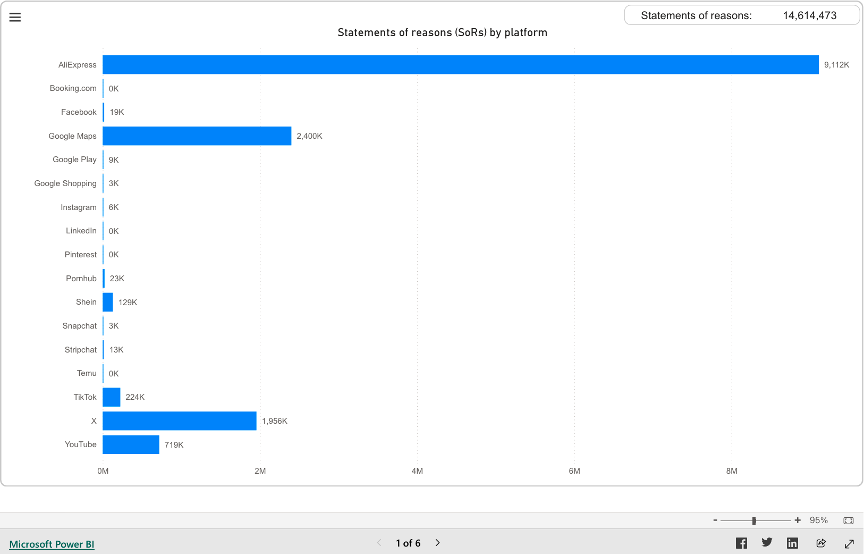

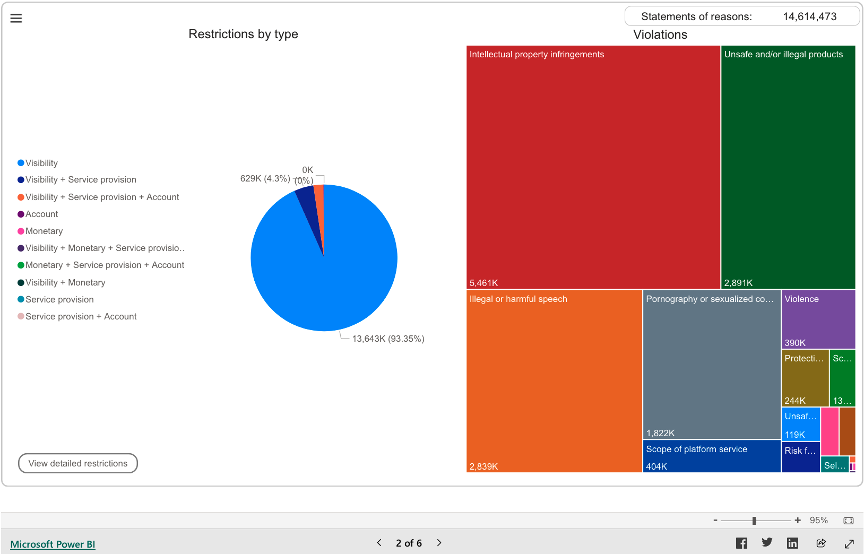

Figure 3: Volume of “Statements of Reasons” for legal violations issued by Very Large Online Platforms and Very Large Search Engines.

The data shows, all Very Large Online Platforms and Very Large Search Engines (Article 33 DSA) all have a clear predominance of ToS in their SoR database entries over actions grounded in specific legal violations, with 33,220,337,157 entries for SoRs based on ToS violations and only 14,614,473 based on illegal content (See Figures 2 and 3). Which means that for every SoR entry based on illegal content, there are about 2,274 SoRs based on ToS violations, or expressed in percent; 99.96% of all entries are based on contractual grounds.

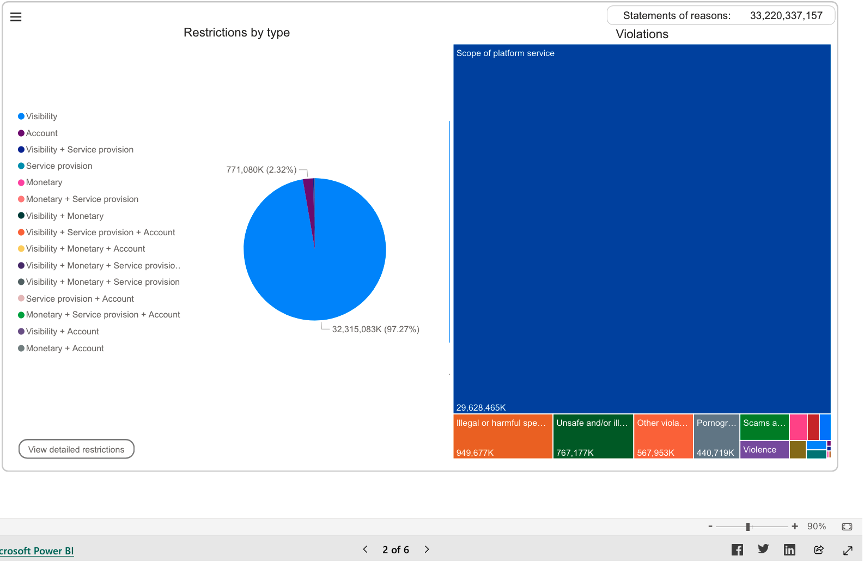

Figure 4: Breakdown of content restriction actions by type and violation category for Terms of Service violations issued by Very Large Online Platforms and Very Large Search Engines.

Figure 5: Breakdown of content restriction actions by type and violation category, legal violations issued by Very Large Online Platforms and Very Large Search Engines.

Also, data indicates that “Scope of platform service” is the dominant category for SoR under ToS, with 29,628,465 entries. When comparing the “Illegal/harmful speech” category across enforcement bases, the difference is stark. Under ToS-based SoRs, this category accounts for 949,677,000 entries, representing 2.86% of all ToS-based SoRs. In contrast, under the illegal content classification, “Illegal or harmful speech” comprises only 2,839,000 entries, or 19.43% of all illegal-content SoRs. In absolute terms, this means there are roughly 335 times more entries for “Illegal/harmful speech” in the ToS category than in the illegal content category. This divergence highlights how platforms overwhelmingly handle such speech through ToS enforcement, where the definitional scope is broader and procedural requirements are lighter, rather than classifying it as a legal violation, which entails more formal obligations.

3. This distribution highlights a form of behavioral harmonization:

Platforms are predominantly enforcing private norms rather than the fragmented landscape of illegality under Member State laws. Demonstrated in Wagner et al,[22] for content moderation on small and medium platforms, or for Facebook and Twitter under the predecessor of the DSA in Germany – the Network Enforcement Act.[23] The DSA’s transparency regime compels them to categorize each takedown, but the prevalence of the ToS implies that for most content removals, companies rely on their global Community Standards as the basis.[24] In effect, a piece of content might be illegal under some EU national law, but the platform often chooses to moderate it under an equivalent provision of its own rules, which can be applied uniformly. [25]

This choice also reflects a strategic business calculus. By relying on Community Standards rather than specific legal provisions, platforms retain greater flexibility to interpret and adjust enforcement in line with their operational and reputational priorities. Platform design choices are also led by differences in complexity for user reporting under the DSA.[26] In that sense, the application of private norms is both a compliance strategy and a business decision; one that may not always align with the European Commission’s vision of harmonized, law-based governance under the DSA.

Strategic Incentives: Global Standards vs. National Fragmentation: Why do online platforms prefer to enforce one set of rules globally rather than deal with divergent national laws? The DSA’s implementation has cast a spotlight on this question, which goes to the heart of the Brussels Effect.[27]

Scalability and Cost-Efficiency: The foremost reason is efficiency. It is vastly simpler and cheaper for a platform like Facebook or YouTube to have a single, uniform code of conduct/Community Standard that applies to all content worldwide. Moderation, especially the review of millions of pieces of user- or AI-generated content, is resource-intensive. Training moderation staff or building AI filters for each country’s unique legal definitions is costly. Platforms instead distill common into their ToS and enforce those uniformly – in set theory, the ToS become the superset of fragmented legal laws.

Reduction of Legal Uncertainty and Liability: Choosing to remove content under a platform’s own rules rather than waiting to assess its illegality under law can also reduce liability exposure. Under the DSA (and previously the e-Commerce Directive),[28] platforms are shielded from liability for user content if they lack “actual knowledge” of illegal material or act expeditiously when notified (See Article 8 DSA). However, if a platform deliberately analyzes content and determines it to be illegal under a specific national law, it might be argued that the platform has knowledge and must remove it everywhere that law applies– or even face potential responsibility for similar content.[29] By contrast, if the platform removes content as a breach of its ToS, it sidesteps an official determination of illegality.

Beyond cost and liability arguments, uniform global rules also reduce uncertainty and lower transaction costs, which can in turn spur innovation. As Aghion et al. note,[30] predictable regulatory frameworks foster investment and experimentation by clarifying the boundaries of competition and reducing coordination frictions. In this sense, the move toward harmonized rules may not only streamline compliance but also reshape the conditions for innovation in moderation technologies and digital governance through the DSA if uncertainties in enforcement and definitions can be overcome.

At the same time, complexity economists such as Arthur[31] and Perez[32] remind us that harmonization can cut both ways. Uniform frameworks can stabilize expectations and enable broad technological diffusion, but they can also produce path dependence, e.g. locking systems into prevailing technological or organizational trajectories through shaping technologies from a social point of view; as for example demanding certain standardization practices, e.g. in the design of illegal content reporting mechanisms under Article 16 DSA. In the context of the DSA, such dynamics raise the question of whether global compliance architectures will foster adaptive innovation or entrench existing moderation paradigms.

Content Moderation at Scale: A related point is the sheer scale of content that large platforms handle.[33] Instagram alone has 1.3 billion images shared daily.[34] Moderating “at scale” is often cited as a near-impossible task;[35] adding a layer of jurisdiction-specific rules multiplies the challenge.[36] The harmful aspects of being exposed to horrible content to human moderators, the need for speed, the complexity of distribution and sheer amount, as well as DSA’s reporting obligations, further encourage investments in automated moderation and compliance tools.

Resource Concentration and Expertise: Handling content under private rules allows platforms to concentrate expertise in-house,[37] rather than relying on 27 different national legal systems to guide moderation.[38] These rules can be updated rapidly in response to new harms (e.g., “we now ban ‘deepfake’ videos of non-existing news events”). This more streamlined approach is using novel regulations as legal basis for process innovation and moderation standardization.

Becoming or being compliant furthermore is a market entry barrier for smaller firms. As Joskow notes, regulatory regimes often interact with existing cost structures in ways that favor incumbents with established compliance infrastructures and sunk investments.[39] Regulatory compliance imposes fixed and recurring costs, such as monitoring, reporting, and certification, that scale less efficiently for smaller entrants, effectively reinforcing monopolistic market structures rather than opening them to competition.

In essence, the DSA has shone a light on a pre-existing trend: platforms governing themselves transnationally.[40] It forces them to document and justify that governance (via statements of reasons, data access, audits), but it does not fundamentally force a renunciation of global rules in favor of local ones – in fact, it arguably also privileges global rules by making the alternative (case-by-case national compliance) more demanding.

The broad definition of illegal content as anything illegal in any Member State (See Article 3 (h) DSA) suggests that if a platform is notified under the DSA about such content, it will remove or disable it EU-wide (to avoid “accessibility” in that – and more – Member States). From a global competitiveness perspective, harmonized moderation simplifies the DSA-aligned process, which is part of the EU’s broader attempt to set uniform rules in Big Tech and foster a more competitive technological playing field for the European market.[41]

The DSA’s role as a quasi-digital-industrial policy instrument carries significant implications for how platforms are built and operated, who can enter or remain in the EU market, and the pace and direction of innovation.

4. Innovation Climate

The debate over Europe’s heavy digital regulation often centers on its impact on innovation. Critics warn of a chilling effect:[42] companies might shy away from developing new features or business models if they anticipate regulatory hurdles or fines. [43] However, it is equally plausible that clear rules of the road enable innovation by providing legal certainty.[44] The DSA harmonizes what is expected of platforms across all Member States, replacing a patchwork of national laws (like Germany’s NetzDG or Austria’s Communication Platforms Law)[45] with one framework. A company now knows that if it complies with the DSA, it can operate EU-wide. This legal clarity and uniformity can reduce compliance costs in the aggregate and allow a company to scale across Europe more easily than before. Furthermore, it aims to create value for users with creating a safer online space and a more transparent handling of content moderation processes within platforms.

Yet this harmonization also produces a dual effect: the DSA could generate both innovation in compliance technologies and innovation deterrence in new platform models that fall outside the standardized regulatory template (e.g. smaller platforms that do not have to conform to systemic risks assessments and more stringent reporting obligations).

These dynamics underscore a broader trade-off at the heart of the EU’s regulatory strategy. By prioritizing legal certainty, uniform standards, and accountability, the DSA lowers barriers for some types of innovation, particularly those aligned with compliance and oversight, but may simultaneously raise barriers for exploratory or decentralized models. The challenge for European policy is thus not simply to balance regulation and innovation, but to ensure that the forms of innovation encouraged by regulation remain diverse enough to sustain long-term competitiveness.

From an innovation-economics perspective,[46] such regulatory harmonization can shape not only the volume but also the direction of innovation. By standardizing procedures and risk-assessment requirements, the DSA may encourage complementary innovation; for instance, in compliance and auditing technologies, while discouraging more radical or product-level experimentation that conflicts with strict liability or procedural constraints. As Galasso & Schankerman show, institutional design conditions where firms channel inventive effort, often steering it toward adaptive rather than disruptive innovation.[47]

Another aspect is innovation in compliance technology itself. The DSA could spur development of better AI content filters (to meet the requirements without squelching too much speech),[48] more sophisticated age verification and parental control systems (as platforms must consider protection of minors),[49] and enhanced auditing tools (for the mandated annual risk assessments).[50] In this sense, the DSA illustrates the dual nature of policy in innovation governance, supporting complementary innovation while constraining radical technological change. European firms might nonetheless take the lead in these compliance-oriented domains, potentially turning regulatory alignment itself into a competitive export advantage.

5. Conclusion

The Digital Services Act exemplifies the European Union’s distinctive approach to digital governance using law and regulatory power as levers to steer the digital economy in line with European values and interests. Far from being merely a set of legal constraints, the DSA functions as a form of industrial policy by other means – one aimed at recalibrating the relationship between global tech platforms and the societies they serve.

Yet this ambition also raises a critical question: given the sheer scale of content decisions and the predominance of firm-specific enforcement under ToS, to what extent do these moderation outcomes actually reflect “European values and interests,” or simply the operational and commercial logics of global platforms adapting to regulatory pressure? The DSA thus operates within an uneasy balance between public oversight and private norm enforcement. Through the DSA, the EU asserts influence in a domain where it lacks native corporate giants, effectively turning regulatory leadership into a competitive asset.

In brief, the DSA demonstrates that regulation can indeed be a form of industrial strategy – setting rules is a way of setting direction. It has made the EU a central actor in digital policy debates and given it a seat at the table to which even the largest corporations must pay heed.

Marie-Therese Sekwenz

PhD candidate at TU Delft’s Faculty of Technology, Policy and Management, where she serves as Deputy Director of the AI Futures Lab on Rights and Justice

Citation: Marie-Therese Sekwenz, EU Digital Regulation as Industry Shaping Policy: The DSA, Brussels Effect, and Global Competitiveness, Industrial Policy and Competitiveness (ed. Thibault Schrepel & Dirk Auer), Network Law Review, Fall 2025.

References:

- [1] Regulation (EU) 2022/2065 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 October 2022 on a Single Market For Digital Services and amending Directive 2000/31/EC (Digital Services Act) (Text with EEA relevance) 2022 (OJ L).

- [2] A Annoni and others, ‘Artificial Intelligence: A European Perspective’ <https://eprints.ugd.edu.mk/28043/1/1.ai-flagship-report-online%20%282%29.pdf?utm_source=consensus> accessed 12 August 2025; ‘Europe’s Digital Decade | Shaping Europe’s Digital Future’ (21 May 2024) <https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/europes-digital-decade> accessed 11 June 2024; ‘Digital Rights and Principles’ (European Commission – European Commission) <https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_7683> accessed 11 June 2024.

- [3] Feng Li, ‘Sustainable Competitive Advantages via Temporary Advantages: Insights from the Competition between American and Chinese Digital Platforms in China’ [2021] British Journal of Management <https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/26875/8/Sustainable%20Competitive%20Advantages%20via%20Temporary%20Advantages%20-%20BJM%20-%20Final%20accepted_.pdf?utm_source=consensus> accessed 12 August 2025.

- [4] Anu Bradford, ‘The Brussels Effect’ in Anu Bradford, The Brussels Effect (1st edn, Oxford University PressNew York 2020) <https://academic.oup.com/book/36491/chapter/321182245> accessed 8 August 2025.

- [5] Kenneth J Arrow, ‘Economic Welfare and the Allocation of Resources for Invention’.

- [6] Richard R Nelson and Sidney G Winter, An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change (Harvard University Press 1985) 23–52, 275–308.

- [7] Joseph A Schumpeter, ‘Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy’ 83.

- [8] Mark A Lemley, ‘Protecting Consumers in a Post-Consent World’ (SSRN, 2025) <https://www.ssrn.com/abstract=5113536> accessed 23 October 2025.

- [9] Staff in the Office of Technology and The Division of Privacy and Identity Protection, ‘AI (and Other) Companies: Quietly Changing Your Terms of Service Could Be Unfair or Deceptive’ (13 February 2024) <https://www.ftc.gov/policy/advocacy-research/tech-at-ftc/2024/02/ai-other-companies-quietly-changing-your-terms-service-could-be-unfair-or-deceptive?utm_source=chatgpt.com> accessed 23 October 2025.

- [10] Stuart A Kauffman, The Origins of Order: Self-Organization and Selection in Evolution (Oxford University Press 1993).

- [11] See Teece et al. (1986) on dynamic capabilities and the co-evolution of firm routines and market structures, and Bresnahan & Trajtenberg (1995) on general-purpose technologies and complementary innovations. Both highlight how standards and institutional choices shape the direction of innovation. The adaptive dynamics described by Kauffman (1993) similarly suggest that large-scale self-regulatory systems, such as biological systems or in the scope of this article too platform moderation regimes, may reinforce certain technological trajectories over others. Teece DJ, Pisano G and Shuen A, ‘Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management’ (1997) 18 Strategic Management Journal 509, Bresnahan TF and Trajtenberg M, ‘General Purpose Technologies “Engines of Growth”?’ (1995) 65 Journal of Econometrics 83.

- [12] Kauffman (n 10) 255–278, 407–419.

- [13] Carlos Diaz Ruiz, ‘Disinformation on Digital Media Platforms: A Market-Shaping Approach’ (2025) 27 New Media & Society 2188.

- [14] The DSA can issue fines of up to 6% of the annual global turnover according to Article 74.

- [15] Annegret Bendiek and Isabella Stuerzer, ‘The Brussels Effect, European Regulatory Power and Political Capital: Evidence for Mutually Reinforcing Internal and External Dimensions of the Brussels Effect from the European Digital Policy Debate’ (2023) 2 Digital Society 5.

- [16] Paul Timmers, ‘Digital Industrial Policy for Europe’ (Centre on Regulation in Europe (CERRE) 2022) <https://cerre.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Digital-Industrial-Policy-for-Europe.pdf> accessed 12 August 2025.

- [17] Nathalie A Smuha (ed), The Cambridge Handbook of the Law, Ethics and Policy of Artificial Intelligence (Cambridge University Press 2025) 133–261 <https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/cambridge-handbook-of-the-law-ethics-and-policy-of-artificial-intelligence/0AD007641DE27F837A3A16DBC0888DD1> accessed 12 August 2025; Sonia Livingstone and others, ‘Maximizing Opportunities and Minimizing Risks for Children Online: The Role of Digital Skills in Emerging Strategies of Parental Mediation’ (2017) 67 Journal of Communication 82.

- [18] Guillaume Beaumier and Lars Gjesvik, ‘Digital Governance in a Rubber Band: Structural Constraints in Governing a Global Digital Economy’ (2025) 5 Global Studies Quarterly 13.

- [19] Marie-Therese Sekwenz and Rita Gsenger, ‘The Digital Services Act: Online Risks, Transparency and Data Access’ (Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co KG 2025) <https://www.nomos-elibrary.de/de/10.5771/9783748943990-115/the-digital-services-act-online-risks-transparency-and-data-access> accessed 1 August 2025.

- [20] ‘Statements of Reasons – DSA Transparency Database’ <https://transparency.dsa.ec.europa.eu/statement?lang=en> accessed 8 August 2025.

- [21] Alberto Galasso and Mark Schankerman, ‘Patents and Cumulative Innovation: Causal Evidence from the Courts’ (2015) 130 The Quarterly Journal of Economics 317.

- [22] Ben Wagner and others, ‘Regulating Transparency? Facebook, Twitter and the German Network Enforcement Act’, Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (Association for Computing Machinery 2020) <https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3351095.3372856> accessed 12 August 2025.

- [23] ‘Act to Improve Enforcement of the Law in Social Networks (Network Enforcement Act)’ 31.

- [24] Marie-Therese Sekwenz, Ben Wagner and Simon Parkin, ‘“It Is Unfair, and It Would Be Unwise to Expect the User to Know the Law!” – Evaluating Reporting Mechanisms under the Digital Services Act’, Proceedings of the 2025 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (Association for Computing Machinery 2025) <https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3715275.3732036> accessed 27 June 2025.

- [25] Ben Wagner and others, ‘Mapping Interpretations of the Law in Online Content Moderation in Germany’ (2024) 55 Computer Law & Security Review 106054.

- [26] Marie-Therese Sekwenz, Ben Wagner and Simon Parkin, ‘“It Is Unfair, and It Would Be Unwise to Expect the User to Know the Law!” – Evaluating Reporting Mechanisms under the Digital Services Act’, Proceedings of the 2025 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (Association for Computing Machinery 2025) <https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3715275.3732036> accessed 27 June 2025.

- [27] Anu Bradford, ‘The Brussels Effect’ in Anu Bradford, The Brussels Effect (1st edn, Oxford University PressNew York 2020) <https://academic.oup.com/book/36491/chapter/321182245> accessed 8 August 2025.

- [28] Directive 2000/31/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2000 on certain legal aspects of information society services, in particular electronic commerce, in the Internal Market (‘Directive on electronic commerce’) 2000.

- [29] Eva Glawischnig-Piesczek v Facebook Ireland Limited [2019] ECJ Case C-18/18.

- [30] Philippe Aghion and others, ‘Competition and Innovation: An Inverted-U Relationship’ (2005) 120 The Quarterly Journal of Economics 701.

- [31] W Brian Arthur, The Nature of Technology : What It Is and How It Evolves (New York : Free Press 2009) <http://archive.org/details/natureoftechnolo00arth> accessed 22 October 2025.

- [32] Carlota Perez, Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital : The Dynamics of Bubbles and Golden Ages (Cheltenham, UK ; Northampton, MA, USA : E Elgar Pub 2002) <http://archive.org/details/technologicalrev00carl> accessed 22 October 2025.

- [33] Tarleton Gillespie, ‘Content Moderation, AI, and the Question of Scale’ (2020) 7 Big Data & Society 205395172094323.

- [34] Kalum, ‘Instagram Statistics in 2025 Every Marketer Should Know’ (Metricool, 25 June 2025) <https://metricool.com/important-instagram-statistics/> accessed 13 August 2025.

- [35] Evelyn Douek, ‘Content Moderation as Administration’ (Social Science Research Network 2022) SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 4005326 <https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=4005326> accessed 13 March 2022.

- [36] Lenka Fiala and Martin Husovec, ‘Using Experimental Evidence to Improve Delegated Enforcement’ (2022) 71 International Review of Law and Economics 106079.

- [37] Jie Cai and others, ‘Content Moderation Justice and Fairness on Social Media: Comparisons Across Different Contexts and Platforms’, Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Association for Computing Machinery 2024) <https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3613905.3650882> accessed 15 May 2025.

- [38] Mia Nahrgang and others, ‘Written for Lawyers or Users? Mapping the Complexity of Community Guidelines’ (2025) 19 Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media 1295.

- [39] Paul Joskow, ‘Regulation of Natural Monopoly’, vol 2 (Elsevier 2007) <https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:eee:lawchp:2-16> accessed 23 October 2025.

- [40] Julie E Cohen, ‘Networks, Standards, and Transnational Governance Institutions’ in Julie E Cohen (ed), Between Truth and Power: The Legal Constructions of Informational Capitalism (Oxford University Press 2019) <https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190246693.003.0008> accessed 9 December 2024.

- [41] Thibault Schrepel, ‘A Systematic Content Analysis of Innovation in European Competition Law’ (28 November 2023) <https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=4413584> accessed 28 November 2023.

- [42] Ioanna Tourkochoriti, ‘The Digital Services Act and the EU as the Global Regulator of the Internet’ Chicago Journal of International Law; Lorcán Price, ‘Written Statement of Lorcán Price Legal Counsel Alliance Defending Freedom International’ <https://www.congress.gov/119/meeting/house/118565/witnesses/HHRG-119-JU00-Wstate-PriceL-20250903-U5.pdf> accessed 23 October 2025.

- [43] Paul Fraioli, ‘Big Tech and the Brussels Effect’ (2025) 67 Survival 173.

- [44] Aurelien Portuese, Orla Gough and Joseph Tanega, ‘The Principle of Legal Certainty as a Principle of Economic Efficiency’ (2017) 44 European Journal of Law and Economics 131.

- [45] Communication Platforms Law 2022 [151/2020].

- [46] Arrow (n 5); Richard R Nelson, An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change (Cambridge, Mass : Belknap Press of Harvard University Press 1982) <http://archive.org/details/evolutionarytheo0000nels> accessed 22 October 2025; Aghion and others (n 30).

- [47] Galasso and Schankerman (n 21).

- [48] Ivan Bakulin and others, ‘FLAME: Flexible LLM-Assisted Moderation Engine’ (arXiv, 13 February 2025) <http://arxiv.org/abs/2502.09175> accessed 2 July 2025; Kurt Thomas and others, ‘Supporting Human Raters with the Detection of Harmful Content Using Large Language Models’ (18 June 2024) <http://arxiv.org/abs/2406.12800> accessed 14 May 2025; Daphne Keller, ‘Facebook Filters, Fundamental Rights, and the CJEU’s Glawischnig-Piesczek Ruling’ (2020) 69 GRUR International 616; Brandon Dang, Martin J Riedl and Matthew Lease, ‘But Who Protects the Moderators? The Case of Crowdsourced Image Moderation’ [2020] arXiv:1804.10999 [cs] <http://arxiv.org/abs/1804.10999> accessed 17 May 2021.

- [49] Livingstone and others (n 7); Kostantinos Papadamou and others, ‘Disturbed YouTube for Kids: Characterizing and Detecting Inappropriate Videos Targeting Young Children’, Proceedings of the international AAAI conference on web and social media (2020) <https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/ICWSM/article/view/7320> accessed 3 November 2023.

- [50] Marie-Therese Sekwenz and others, ‘Can’t LLMs Do That? Supporting Third-Party Audits under the DSA: Exploring Large Language Models for Systemic Risk Evaluation of the Digital Services Act in an Interdisciplinary Setting’, Adjunct Proceedings of the 4th Annual Symposium on Human-Computer Interaction for Work (Association for Computing Machinery 2025) <https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3707640.3731929> accessed 9 July 2025.