The Network Law Review is pleased to present you with a special issue curated by the Dynamic Competition Initiative (“DCI”). Co-sponsored by UC Berkeley and the EUI, the DCI seeks to develop and advance innovation-based dynamic competition theories, tools, and policy processes adapted to the nature and pace of innovation in the 21st century. This special issue brings together contributions from speakers and panelists who participated in DCI’s second annual conference in October 2024. This article is authored by Frederic Jenny, Emeritus Professor of Economics, ESSEC Business School, and Senior Fellow of the GW Competition and Innovation Lab, The George Washington University.

***

Merger control has been traditionally focused on the impact of the structural changes induced by the mergers examinedon the incentives of the merging parties. Agencies have also long considered the risks that increased market power for the merging parties could lead directly or indirectly to a weakening of price competition. However, recently, competition authorities dealing with mergers in hi-tech industries have started to focus on the potential effect of these mergers on innovation.

The EC merger guidelines[1] recommend analysis of R&D efforts between merging parties to assess the effects of competition on innovation competition. They state: “38. In markets where innovation is an important competitive force, a merger may increase the firm’s ability and incentive to bring innovations to the market and, thereby, the competitive pressure on rivals to innovate. Alternatively, effective competition may be significantly impeded by a merger between two important innovators, for instance, two companies with ‘pipeline’ products related to a specific product market. Similarly, a firm with a relatively small market share may nevertheless be an important competitive force if it has promising pipeline products”.

This paper explores the extent to which capability analysis can inform competition authorities’ analysis when they assess mergers’ effect on innovation. In a first section we show how the EC Dow Dupont merger decision([2]), which included for the first time a systematic analysis of the innovation capabilities of the various players in the crop protection sector, was based on a somewhat simplistic consideration of the unilateral effect of the merger on the incentive of the merging parties to innovate. In a second part, we show that since that decision, the analysis of the effects of a merger on the incentives to innovate has become more sophisticated and that it is now acknowledged, at least by some competition authorities, that merger analysis should consider a variety of possible effects on incentives to innovate. In the third section, we argue that in addition to the effect of mergers on incentives to innovate, the financial and technologicalcapabilities of the merging firms and their competitors should be considered to assess the effect of mergers on innovation. We show that the empirical literature on business economics can provide helpful guidance on how to assess these capabilities. In the final section, however, looking at the poor performances of Boeing post-merger with McDonnell Douglas, we ask how the managerial capabilities of the merging firms and of their competitors to innovate, which also matter, can be taken into consideration in the context of merger control.

1. The Dow Dupont merger decision and the dynamic nature of the effect of a merger on innovation[3]

The EU Dow Dupont merger decision was at the center of a vigorous debate on the analysis of the effects of mergers in dynamic industries on innovation. As stated by the Decision (paragraph 349): “First, the assessment of innovation competition requires the identification of those companies which, at an industry level, do have the assets and capabilities to discover and develop new products which, as a result of the R&D effort, can be brought to the market.” The Commission conducted a careful analysis of the capabilities of potential competitors concerning innovation at three levels: first, competition between existing products and pipeline products; second, competition between R&D projects for new active ingredients in the relevant innovation space; and third, innovation in competition at the crop protection level.

The Decision reviewed the R&D capabilities of the competitors. It determined that the merger would likely reduce innovation competition in the crop protection industry by discouraging research efforts and cutting early-stage pipeline projects. This reduction in innovation incentives could lead to fewer new products, significantly impacting herbicides, insecticides, and fungicides, with an estimated drop in new active ingredients by more than one every two years. The findings of the Commission were essentially based on the idea that a merger between two key innovators can reduce competition in innovation, ultimately slowing the overall rate of innovation because, when firms compete to introduce new products, they create a “negative externality” for rivals by capturing market share. A merger internalizes this effect, making the potential loss of profits from the other merging firm an opportunity cost of innovation. As a result, without merger-specific efficiencies, both firms have lower incentives to innovate.

Implicitly, the view is that product market competition is good for innovation. The more competing R&D programs exist and the better they are funded, the more likely innovation will develop. However, various commentators have criticized this approach as being incomplete. Denicolò and Polo[4] note that if, for the Commission, mergers generally have a negative impact on innovation by reducing investment in competing R&D projects, they can also spur innovation through other mechanisms. That same year, Bruno Jullien and Yassine Lefouili (2018)[5] explored the innovation effects that can result from a horizontal merger. They note that “ (…) a static analysis of innovation is necessarily reductionist because of the fundamentally dynamic nature of the innovation process. This process is cumulative both at the firm level and the industry level (Scotchmer, 2004), which implies that a structural change, such as a merger, may have a long-lasting effect on innovation”.

They explain that whereas a merger aligns the incentives of the merging entities to maximize joint profits, leading each to internalize the impact of its decisions on the other, when innovation is involved, the analysis becomes more complex as innovation alters technologies and product lines, but clarity is achieved by first assessing incentives and then considering changes in ability. They describe various possible direct effects of a merger on innovation. First, the innovation diversion effect resulting from a firm’s innovation’s impact on its rival’s sales, can be either positive or negative. Second, the demand expansion effect, is positive; it rests on the idea that the margin increase induced by a merger provides the merging firms with higher incentives to innovate to increase their demand. Third, the margin expansion effect, which results from the decrease in the merging firm’s output, in the absence of efficiencies, lowers the firm’s incentives to innovate to increase their margins (by setting higher prices). Finally, the spillover effect results from the fact that a firm’s investment in R&D may benefit its rivals through technological spillovers, thus possibly resulting in an increase in innovation with the merger.

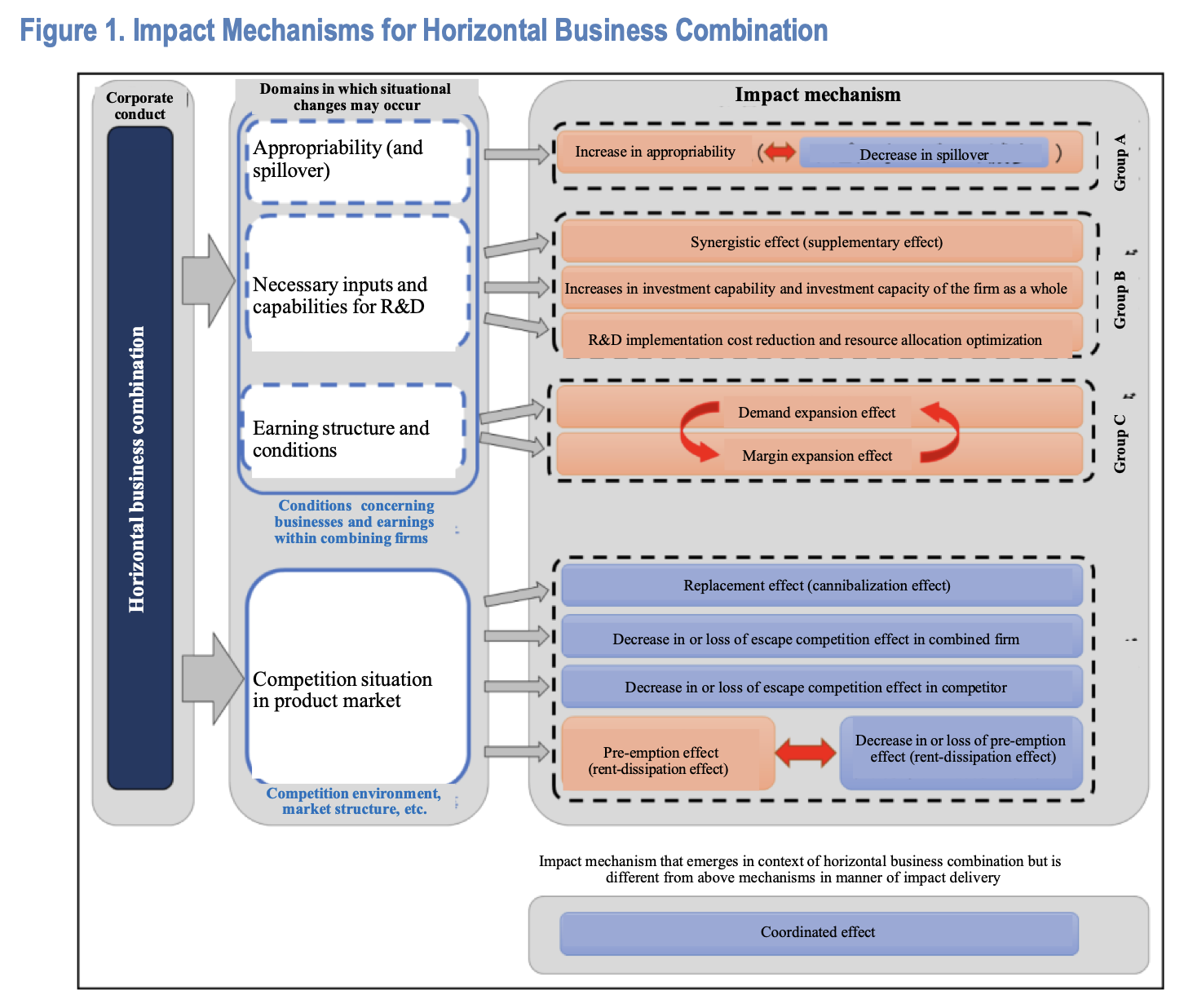

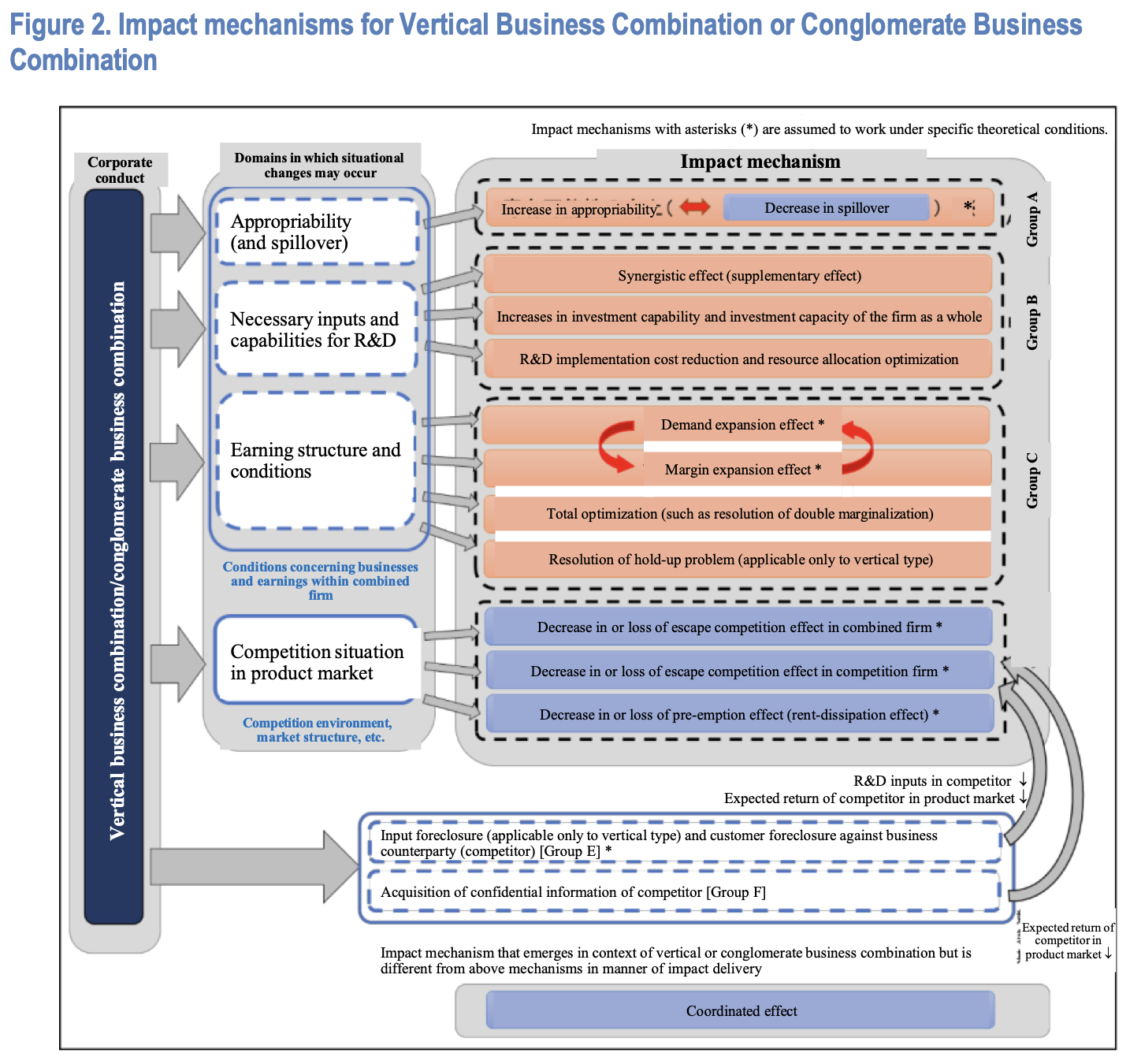

Some competition authorities have seriously considered the Jullien Lefouili characterization of the forces at work concerning mergers in a dynamic industry. For example, the Japanese contribution to a debate at the OECD Competition Committee on Innovation and Competition held in December 2023[6] referred to the report of a study group of economists convened by the Japanese Fair Trade Commission to study this question. The report analyzed both the case of horizontal mergers and the case of vertical or conglomerate mergers. It summarized the effects noted by the study group in the following diagrams where the orange boxes denote a possible positive impact of the merger on innovation and blue a potential negative impact[7].

As can be readily seen in both tables, most of the positive impacts of the merger on innovation come from the possible reorganization of assets and resources within the parties to the merger and from adjustment of the profit-maximizing strategy of the merged firm, whereas most of the potentially harmful effects of a merger on innovation come from modifications of the incentives of the market participants due to the structural changes created by the merger. A merger analysis focusing exclusively on the changes in incentives following a merger and which does not investigate the possible reorganization of the competence and resources between the merging firms is thus likely to be biased against the merger.

One should note that the definition of the dynamic nature of the innovation process proposed by Jullien and Lefouili differs from the concept of dynamic capabilities developed by Teece and others. Jullien and Lefouili refer to the cumulative effect resulting from the fact that innovation decisions will change products and production processes and that these changes will have a secondary impact on the price and innovation decisions of the merging firms and their competitors. But implicit in the Jullien and Lefouili approach is the fact that the quantity of innovation to be expected in the case of a merger is uniquely dependent on the RD spendings of the merged firms and that this spending on R&D of the merged firms will be greater or smaller than the pre-merger spendings on R&D depending on how the incentives of the merging firms are affected by the merger.

2. The dynamic capabilities approach

David J. Teece, Gary Pisano, and Amy Shuen[8] do not focus principally on R&D spending but on what they see as the differentiated innovation capabilities of the firms faced with rapid technological change. They view the innovation process not as an automatic reaction to changing incentives resulting from modifications of the market constraints in which the firm operates but as a process allowing the merged firm to recombine competencies and resources to address its changing environment. They state: “(…) Only recently have researchers begun to focus on the specifics of how some organizations first develop firm-specific capabilities and how they renew competencies to respond to shifts in the business environment. These issues are intimately tied to the firm’s business processes, market positions, and expansion paths. Several writers have recently offered insights and evidence on how firms can develop their capability to adapt and even capitalize on rapidly changing environments. The dynamic capabilities approach seeks to provide a coherent framework which can both integrate existing conceptual and empirical knowledge, and facilitate prescription”.

In their view, all firms are not equal when it comes to innovation. Their differences will shape their ability to innovate and the way innovation develops, altering competition between the firms in the market. Thus, understanding the ultimate effect of a merger on competition and innovation cannot be limited to assessing how the players’ incentives interact concerning their decisions on pricing and on R&D market spending but also requires the consideration of the capabilities of the merging firms and their competitors to innovate. Along the same lines, competition and innovation specialists Nicolas Petit, Thibault Schrepel and Bowman Heiden[9] have argued: “A focus on capabilities can tell if the merging firms enjoy alone (or in combination with others) the technological, managerial and financial capabilities required for organic growth.”

Despite these scholarly developments, the dynamic analysis of mergers in hi-tech industries has not progressed noticeably, irrespective of whether one adopts the Jullien Lefouili careful approach of the simultaneous changes in incentives or the more ambitious dynamic capabilities framework advocated by Teece and al. One of the reasons the “dynamic capabilities analysis” has not gotten more traction in competition enforcement may be because it does not seem to offer clear guidance to competition authorities as to where they could get the reliable information needed to assess the different impacts on innovation when they investigate a merger in high technology markets. In contrast, the classic (static) competition approach seems to focus competition authorities on clear and easy to grasp questions: what are the relevant markets likely to be affected, by how much will concentration increase, are barriers to entry high, what is the state of potential competition and to what extent are the incentives of the merging firms and of their competitors likely to be modified by the transaction when it comes to pricing or to invest in R&D.

Even in the case of Japan, the framework laid out by the study group of economists convened in 2023 at the request of the JFTC and mentioned earlier has not been operationalized and has not become a map routinely followed by the JFTC. As has been widely recognized, the challenge for the advocates of the dynamic capabilities framework is to identify objective indicators and data points for capabilities evaluations. Nicolas Petit, Bowman Heiden, and Thibault Schrepel indicated[12], “A focus on capabilities can tell if the merging firms enjoy alone (or in combination with others) the technological, managerial, and financial capabilities required for organic growth.” It is generally relatively easy for competition authorities to assess whether the merging firms or their competitors have the financial capabilities to sustain innovation (even if there can be surprises, as there was recently with the fact that DeepSeek was able to demonstrate that advanced AI capabilities can be achieved with minimal financial resources).

It is more complex for a competition authority to assess the extent to which the merging firms and their competitors have the internal technological and managerial capabilities required for organic growth through innovation or have access to such capabilities. Yet it is necessary to engage in such an analysis if one believes, as Teece, Pisano and Chuen do[11], that: “what a firm can do is not just a function of the opportunities it confronts, it also depends on what resources the organization can muster.” The analysis of the technological and managerial resources of the merging firms then becomes necessary to be able to pass judgment on whether they could grow and innovate independently of the merger ( in which case the merger cannot be justified on the ground of innovation) or if they could not grow and innovate independently of the merger and if competitors could not innovate to the same extent or at the same level of quality as the merged firm would be able to (in which case the merger should be seen as bringing both innovation and, as a consequence, increased competition to the market).

3. Empirical research on firm capabilities

Empirical academic research, generally ignored by competition authorities, could help them develop the tools they need to assess the relative technological capabilities of the various actors on the market, at least in some hi-tech sectors. For example, Marianna Makri, Michael A. Hitt, And Peter J. Lane[12] explore the question of the possible complementarity in the scientific and technological knowledge of merging firms. They study a 1996 sample of 95 high-technology M&As to test the effects of knowledge similarities before the M&A on invention quantity and quality three to five years later. In this process they measure invention activity by the number of patents before and after the mergers, invention quality by the number of the firm’s patent citations in subsequent patents and, finally, they measure invention novelty by the extent to which an index of technological diversification similar to a Herfindahl index of concentration of a firm’s patent portfolio across technology classes increases post-merger. Their study shows, first, that acquisitions can contribute to higher-quality inventions if the appropriate knowledge is acquired. Second, the research emphasizes the importance of knowledge complementarity for the success of high-technology acquisitions. Third, their research introduces an objective measure of knowledge relatedness that distinguishes between science and technology relatedness. The indicators used by the authors could be adapted by competition authorities, at least in sectors where patenting is common, to assess the complementarities of scientific and technological knowledge of merging firms and their competitors.

In fact, in 2017 in the Dow/Dupont EC decision, the EC Commission used a methodology fairly similar to the one suggested by Marianna Makri , Michael A. Hitt, And Peter J. Lane to assess the potential competitors of Dow/Dupont. As Wolfgang Kerber and Simonetta Vezzoso indicate[13], the EU Commission assessed Dow and DuPont’s innovation capabilities by analyzing the strength and quality of their patent portfolios, including patent citations and past successes in launching new active ingredients (Ais) and this approach served as a proxy for their current and future innovation potential in the crop protection industry, improving the Commission’s methods for evaluating firms’ innovation capabilities.

Another recent example of management research that could be useful for competition authorities is Johann Peter Murmann and Fabian Vogt[14] analysis of “A Capabilities Framework for Dynamic Competition,” which builds on the previous work of David Teece. In their paper, they offer a framework to analyze the likelihood that incumbent firms will successfully make the required transformations to their strategy and operations in the face of technological transformations. They observe that to answer this question, one has to look not only at their dynamic capabilities (which allow them to change) but also at the ordinary (i.e., operational) capabilities of the potential entrants to offer the new technology at scale. Indeed, in the face of technological disruption, whereas the incumbents may need to change themselves (use their dynamic capabilities to adapt to the interruption), the entrants need to quickly build their ordinary capabilities to offer the new technology at scale. They apply this framework to assess dynamic competition in the automotive industry where the electric vehicle paradigm requires three types of ordinary and dynamic capabilities (technological capabilities, business models, and market capabilities) and they compare three types of firms: an incumbent (such as Volkswagen), a diversifying entrant (such as Google) and a start-up (such as Tesla in its early days).

The most significant gaps for the incumbents are in software capabilities which they would need to overcome by recruiting experienced but expensive software talent. In contrast, the potential diversifying entrants would lack capabilities associated with the design and manufacturing in the automotive industry. The start-ups would face considerable challenges in establishing a brand at the required scale. Altogether, the authors conclude that the incumbents have a strong position in the US and Europe. This type of analysis would make one wary of the effect of a merger between incumbents on innovation in the automotive sector.

Over and beyond the articles discussed previously, other sources could provide helpful information for competition authorities to assess the technological capabilities of firms in various sectors. As mentioned by Almudena Arcelus, Aaron Fix and Kevin Feeney[15]: “The business and management literature is becoming familiar with capabilities ratings, rankings, and scores. All provide useful methods to answer the complementary question posed by a dynamic competition perspective”. What is less clear is where competition authorities could obtain reliable data on the managerial capabilities of merging firms or of their competitors even if such managerial capabilities (which refer to the capacity of the firm’s managers to run the organization and to make and implement the strategic and operational decision through an impact on and coordination of other firm resources, inputs, and capabilities) can be important for the future development of innovation and competition. Even if such data can be found, one of the problems in assessing the managerial capabilities of a firm is that such capabilities may be very dependent on the presence of specific managers who can leave the firm fairly rapidly either because they are dismissed or because they lose a power struggle or because they retire or because they find a better offer in another firm.

4. The Boeing/McDonnell merger and the managerial capability analysis

A retrospective example, the 1997 merger between Boeing and McDonnell Douglas, suggests both the potential usefulness of the dynamic capabilities approach and the complexity associated with considering the merging firms’ managerial capabilities to assess the merger’s potential effect on innovation.

Boeing, which operated in two principal areas: commercial aircraft and defense and space, wanted to acquire the McDonnell Douglas Corporation, which operated in four areas: military aircraft; missiles, space, and electronic systems; commercial aircraft; and financial services (but derived 70% of its revenue from its military and space businesses). This 3 to 2 merger was very controversial. Boeing had a large share of the world and European market for large commercial jet aircraft (which included two relevant markets, the market for narrow-body aircraft and the market for wide-body aircraft) before the merger (with market shares of 64% at the world level and 61% at the European level) and would see its global market share increase by 6 % and would be left with only one competitor (Airbus).

The US FTC cleared the merger, whereas the EU Commission was concerned that the merger would strengthen the dominant position of Boeing and reduce competition on the market for narrow-body and wide-body civilian aircraft, imposed commitments. It is interesting to note that even though, as we shall see, the development of the market for large civil aircraft is essentially due to innovations in aircraft, the dominance of Boeing alleged in the EU decision is purely based on its historical market shares and not on its capabilities to innovate (see paragraphs 38 to 52 of the Decision). Even though the analysis of the merger by the European Commission was mostly centered on the issues of the possible impact of the merger on its dominant position, one can find in its Decision elements of a dynamic capabilitiesanalysis. The Commission’s Decision suggests that the Commission considered that the merger would increase the technological, financial, and managerial capabilities of the merging parties over and beyond what these capabilities would be without the merger.

For example, the decision states:

1. that McDonnell Douglas does not have any commercial capability left:

“57. However, since, as outlined below, MDC is no longer a real force in the market for commercial aircraft, and in the absence of another potential buyer of its commercial aircraft business, it is likely that Boeing would have obtained, over time, a monopoly in the 100-120 seats segment and a near monopoly in the freighter segment even without the present concentration”;

2. that Boeing’s resources for the development of civilian aircraft would benefit from the spillover effect of MacDonnell Douglas defence and space business;

“53. The proposed concentration would lead to a strengthening of Boeing’s dominant position in large commercial aircraft through : (…) the large increase in Boeing’s overall resources and in Boeing’s defence and space business which has a significant spillover effect on Boeing’s position in large commercial aircraft and makes this position even less assailable” “70. More generally, Boeing’s broader product range after the merger, its financial resources, and its higher capacity, which enables it to respond to airlines’ needs for deliveries on a short lead time, would, in combination, significantly increase Boeing’s ability to induce airlines to enter into exclusive deals. It should be noted that it would be impossible for Airbus to offer exclusive deals because Airbus is unable to offer a full “family” of aircraft”.

3. that there was skepticism about the commitment of McDonnell Douglas to the civilian aircraft business and/or its ability to innovate;

The decision indicates[16] that in 1996, if Douglas Aircraft Company (DAC) earned $100 million in operating income, most of its earnings came from spare parts and product support rather than new aircraft sales. Unlike Boeing and Airbus, DAC offered only four aircraft models—three narrow-body and one wide-body—which were derivatives of older designs and lacked significant commonality benefits.

4. that, however, Boeing could revive the confidence of customers in the McDonnell Douglas aircraft and its commitment to the large civilian aircraft market;

The decision suggests[17] that Boeing’s acquisition of DAC initially offered the possibility of continuing DAC’s aircraft production, potentially improving its market perception and integration with Boeing’s sales strategy.

5. that the acquisition by Boeing of the McDonnell Douglas overcapacity would allow Boeing to be more flexible in meeting the demand of customer airlines[18];

6. that the overall effects resulting from the defence and space business of MacDonnell Douglas would lead to a strengthening of Boeing’s position concerning technological knowledge and manufacturing capabilities and to a net strengthening of capabilities of the civil aviation sector[19];

7. and that the combination of the intellectual property of the two companies would be crucial for the ability of the merged firms to innovate notably in aircraft structures, composites, aerodynamics, flight controls and electricity and electronics[20].

In short, besides the competition concerns expressed in the Decision regarding the market dominance of Boeing, its buying power, the long-term exclusivity deals it has signed with several US airlines, and its ability to block access to significant technological advances thanks to its patent portfolio, the analysis of the Commission is that the merger would significantly increase the technological and financial capabilities of the merging parties (compared to what would happen without the merger)

This leads us to formulate two observations: The first observation is that in the EC Decision, it is quite clear that the increase in the financial and technological capabilities of the merging parties due to the merger is analyzed as a factor reinforcing their market dominance (and therefore justifying a reticence toward the merger) rather than a factor favorable to an intensification of competition through innovation between Boeing and Airbus (justifying approval of the merger). The second observation is that there is very little information in the Commission’s Decision about the merger’s impact on the merged firm’s managerial capabilities. Yet, it seems clear that following the merger, Boeing has lost a lot of grounds to its competitor Airbus for reasons which seem related to managerial difficulties within the merged firms[21].

In 2011, American Airlines considered placing an order with Airbus for the A320 Neo aircraft which was more fuel-efficient than the Boeing 737. Boeing’s head of commercial aviation proposed to design a new single-aisle aircraft to replace the Boeing 727 (which had been certified in 1964), the Boeing 737 (which had been certified in 1968), and the Boeing 757 (which had been certified in 1972), which would incorporate all the advances in aviation technology. However, Boeing leadership chose, instead of spending $20 billion on a new plane, to allocate a budget of $2.5 billion for a five-year program to upgrade the 737 (737 Max) while keeping the original design so that pilots wouldn’t have to be retrained. Technical drawings for the model were delivered at a high speed, and workers from other departments were brought in to work on the Max project. Timely delivery took precedence over quality.

In 2015, the 737 Max encountered stall problems due to aerodynamic changes from new, more fuel-efficient engines. Boeing opted to solve the problem by adopting a major software change rather than by a change in design that would have put in jeopardy the 737 certification. However, the software’s reliance on data from a single sensor turned out to be the main weakness of Boeing. In 2018 and 2019, two crashes killed 346 people. The 737 MAX was grounded again on January 5, 2024, after a mid-air blowout of a fuselage panel. After loose bolts were discovered on other MAX 9s, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) grounded the planes and opened an investigation into whether MAX is safe to fly. Airbus sales have surpassed Boeing’s sales for the last five years.

The reasons which led to these events are widely attributed to the fact that with the merger came a change both in the management team and in the culture of Boeing. This change came about because executives from McDonnell Douglas (who came from a financially struggling company) filled Boeing’s top jobs and shifted the company’s engineering-centric corporate culture to one focused on profitability, cost control, and shareholder value. Accountants, who are very sensitive to shareholders’ wealth and not engineers, started making major decisions. The former Boeing CEO Harry Stonecipher (who came from McDonnell Douglas) is reputed to have said, “When people say I changed the culture of Boeing, that was the intent, so that it’s run like a business rather than a great engineering firm”. To cut costs Boeing started outsourcing much of its production to focus on assembly. In 2001 the management headquarters were moved away from where all the engineering took place — from Seattle to Chicago.

This shift from an engineering and safety-centric approach to one driven by financial motives and market pressures is said to have significantly changed the company and undermined its legacy of product excellence. Boeing subsequently faced substantial challenges in maintaining its reputation for quality and safety in aircraft manufacturing. Bill George[22] adds: “When we discuss the Boeing cases in my classes at Harvard Business School, I ask participants, “Are Boeing’s problems caused by individual leadership failures or a flawed culture?” The answer “both” eventually emerges. It was the actions of Condit[23] and Stonecipher[24]. that turned Boeing’s culture from excellence in aviation design, quality, and safety into emphasizing short-term profit and distributing cash to shareholders via stock buybacks. McNerney[25] compounded the problem through his decision to launch a quick fix to the 737 rather than design a new airplane. Muilenburg[26] was left with the flawed aircraft but failed to ground the planes after the first crash and pinpoint the root cause of the failure. The Boeing board, which is composed of exceptional individuals, failed to preserve Boeing’s culture and reputation”. Assuming that the analysis mentioned previously holds some truth, the Boeing McDonnell Douglas merger led to a decrease in the quantity and quality of innovation in the market for large civilian aircraft due to the alteration of the managerial capabilities of the merged firm.

5. Conclusion

Members of the competition community (including both competition economists and competition authorities) voice two reservations about the usefulness of the dynamic capabilities approach in competition law enforcement. First, they claim that this approach does not bring anything new to the extent that competition authorities have long considered the interrelationship between competition and innovation. Second, they argue that the dynamic capabilities approach does not allow sufficiently precise predictions to serve as a basis for law implementation.

On the first issue, however, it is clear that a change of perspective concerning merger control and innovation occurs at the level of competition authorities. As we saw, while looking at the Japanese experience, some competition authorities now accept that increases in concentration may have multiple and contradictory effects on the incentives of the merging firms and of their competitors to innovate and that they should consider the interactions between these effects. They are willing to assess the positive impact of mergers on innovation as a possible benefit rather than exclusively as an indicator of potential increased market power for the merging firms. This may fall short of considering that the innovation brought about by the increased innovation capabilities of the merging firms should be seen as the driver of innovation competition (as emphasized by the dynamic capabilities approach). Still, it is a necessary first step in that direction.

On the second issue, it is also clear that some competition authorities have been willing to consider the dynamic capabilities approach, as we noted when commenting on the Dow/Dupont EC decision. However, it is unclear whether the dynamic capabilities approach can provide the convincing evidence required to assess whether a merger should or should not be blocked. The standard of proof required from the US competition agencies to prohibit a merger is a ” preponderance of evidence” standard. In other terms, the authorities have to show that it is more likely than not that the merger will substantially restrict competition. In the European Union, the Commission has to prove its case based on evidence that is factually accurate, complete, abundant and consistent. In addition the negative effects on competition stemming from a merger must be demonstrated with a sufficient degree of probability.

When considering, for example, a horizontal merger, the question is whether the analysis showing that the merging firms have, through their merger, acquired (or lost) innovation capabilities compared to what would have happened without the merger (and/or compared to their competitors) tells us enough about whether it is more likely than not that the innovation competition associated with the merger will compensate a possible increase in the market power of the merging firms. Two questions must be considered: first, can we relatively easily get reliable indicators of the changes in the dynamic capabilities of the merging firms, and second, is it more probable than not that those changes in capabilities will translate into innovation performances? As we saw, research in business management seems to be helpful (although insufficiently developed) to allow competition authorities to develop frameworks to analyze the technical and financial capabilities of merged firms and compare them to the capabilities of the merging firms and or their competitors. However, as the Boeing McDonnell Douglas example suggested, the managerial capabilities of the merged firm ( or of its competitors) may be more difficult to assess.

A last question worth asking is, what should be the time frame of the innovation competition analysis given the standard of proof? Innovation competition is likely to be an essential but long-term phenomenon, whereas increases in market power are likely to be felt in the short term. Competition authorities have, in the past, consistently argued that the longer the analysis’s time frame, the less reliable the predictions are. As a result, they have tended to consider dynamicefficiency benefits as being speculative and they have focused on short-term (market power) effects.

In a series of decisions starting in 2014 (Medtronic/Covidien[27], Novartis/GSK[28], Pfizer Hospira[29] and Dow/Dupont[30], the European Commission has nevertheless started to consider the long-term effects of mergers on competition and innovation. This has raised the alarm of some commentators who have argued that the longer time horizon of the merger analysis risks undermining the legal certainty, a fundamental principle of the EU merger control system.

As mentioned by Thibault Schrepel and Teodora Gorza[31], competition authorities have started using computational tools hoping that data from previous mergers could be used to train algorithms to predict effects on R&D and innovation. Some competition authorities have already created databases of past decisions to train algorithms in identifying innovation-related concerns. The use of such tools may clearly allow the competition authorities to identify which mergers deserve a particularly close scrutiny because they could potentially be anticompetitive. But it is doubtful that competition authorities could rely on the indications given by such tools to assess the potential dynamic efficiencies associated with mergers to the requisite standard of proof. This means that it is all the more important to develop rapidly a framework facilitating the implementation by competition authorities of the dynamic capabilities approach when they assess the possible impact of mergers on innovation in high-tech industries.

***

| Citation: Frederic Jenny, Dynamic Capabilities Analysis and Merger Control: Is A Long-Delayed Convergence Finally on The Way?, Network Law Review, Spring 2025. |

References:

- [1] “Guidelines on the assessment of horizontal mergers under the Council Regulation on the control of concentrations between undertakings (2004/C 31/03)

- [2] CASE M.7932 – Dow / Dupont, Commission Decision of 27.3.2017 declaring a concentration to be compatible with the internal market and the EEA Agreement

- [3] CASE M.7932 – Dow / Dupont, Commission Decision of 27.3.2017 declaring a concentration to be compatible with the internal market and the EEA Agreement

- [4] Vincenzo Denicolò and Michele Polo “The innovation theory of harm: An appraisal”, Bocconi Working Paper, 2018: “For the Commission, the impact of mergers on such innovation spaces is generally negative. In the Dow-DuPont Decision, for instance, the Commission writes: The merger between (two firms) will result in internalization by each merging party of the adverse effect of the R&D projects on […] the other merging party; hence, […] it will reduce investment in the competing R&D projects. The innovation competition effect [of a merger] follows the basic logic of unilateral effects, which is equally applicable to product market competition and to innovation competition,” and they state that: “ There do exist mechanisms whereby mergers reduce innovation, but there are also others by which mergers spur innovation. Both mechanisms are sound, robust, and empirically relevant, not simply theoretical curiosities”.

- [5] B Jullien and Y Lefouili, “Horizontal Mergers and Innovation” TSE Working papers, August 2018 “

- [6] The Role of Innovation in Enforcement Cases – Note by Japan, OECD Competition Committee, Competition and Innovation roundtable, 5 December 2023

- [7] The Role of Innovation in Enforcement Cases – Note by Japan, OECD Competition Committee, Competition and Innovation roundtable, 5 December 2023 page 4 and page 11

- [8] David J. Teece, Gary Pisano, and Amy Shuen: “Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management “, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 18:7, 509—533 (1997)

- [9] Nicolas Petit, Thibault Schrepel, and Bowman Heiden. “Situating The Dynamic Competition Approach.” Dynamic Competition Initiative (DCI) Working Paper (2024): 1-2024

- [10] Cf Note 7

- [11] Cf Note 6

- [12] Marianna Makri, Michael A. Hitt, And Peter J. Lane, Complementary Technologies, Knowledge Relatedness, And Invention Outcomes In High Technology Mergers And Acquisitions , Strategic Management Journal Strat. Mgmt. J., 31, 602–628 (2010)

- [13] Kerber, Wolfgang and Vezzoso, Simonetta, Dow/Dupont: Another Step Towards a Proper Assessment Concept of Innovation Effects of Mergers (June 24, 2019). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3856885 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3856885:

- [14] Johann Peter Murmann and Fabian Vogt, “A Capabilities Framework for Dynamic Competition: Assessing the Relative Chances of Incumbents, Start-Ups, and Diversifying Entrants”, Management and Organization Review 19:1, February 2023, 141–156

- [15] Almudena Arcelus, Aaron Fix and Kevin Feeney: “Innovation competition assessment by competition Authorities” , Analysis Group, Inc, Practical Law UK, 06-Aug-2020

- [16] Paragraph 59.

- [17] Paragraph 61.

- [18] Paragraph 67. .

- [19] Paragraph 92 , 93 and 101

- [20] Paragraph 102

- [21] See for example Natasha Frost, “The 1997 merger that paved the way for the Boeing 737 Max crisis”, Quartz, January 3, 2020; Did a 1997 merger ruin Boeing? Finshot, January 10, 2024; Aram Gesar, “Boeing’s Shift from Engineering Excellence to Profit-Driven Culture: Tracing the Impact of the McDonnell Douglas Merger on the 737 Max Crisis”; Airguide, January 13, 2024; Bill George, “Why Boeing’s Problems with the 737 MAX Began More Than 25 Years Ago” Working Knowledge, Harvard Business School, January 24, 2024; Yves L. Doz and Keeley Wilson, “Boeing’s Tragedy: The Fall of an American Icon,” INSEAD Knowledge, January 31, 2024; Naresh Sekar, “The Case of Boeing and McDonnell Douglas Merger: Building and Leading Teams”; Case Study, Medium, June 14, 2024.

- [22] Bill George, Why Boeing’s Problems with the 737 MAX Began More Than 25 Years Ago, Working Knowledge, Harvard Business School, January 24, 2024

- [23] Chair and Chief executive officer (CEO) of the Boeing company from 1996 to 2003

- [24] President and Chief Executive officer of McDonnell Douglas from 1994 to 1997 and then President and Chief Operating Officer of Boeing from 1997 to 2001, Vice Chairman of Boeing from 2001 to 2002, President and chief executive officer of Boeing from 2003 to 2005

- [25] Chief executive officer of 3M from 2000 to 2005, President and CEO of the Boeing Company from 2005 to July 2015

- [26] President of Boeing from 2013 to 2018 and Chairman of Boeing from 2015 to 2019

- [27] Case N° M.7326 – MEDTRONIC/ COVIDIEN, 28 November 2014

- [28] Case N° M.7275 – NOVARTIS/ GLAXOSMITHKLINE ONCOLOGY BUSINESS, 28 January 2015

- [29] Case N° M. 7559 – Pfizer / Hospira, 4 February 2015

- [30] Case N° M.7932 – DOW / DUPONT, 27 March 2017

- [31] Thibault Schrepel and Teodora Gorza: « Computing »Innovation Competition », Amsterdam Law and technology Institute, October 2024, accessible at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4985079