Abstract: Our research examines how employee collaboration networks within companies affect the quality of innovation, using data from over 28,000 employees at a large IT services firm. We find that employees who collaborate with more colleagues produce higher-quality innovation, and those who act as “brokers”—connecting otherwise separate groups—create benefits for their entire network. Just being part of a large network doesn’t improve innovation quality; what matters is the number of direct collaborators and one’s role in connecting different groups. The shift to remote and hybrid work disrupted these networks, suggesting companies must actively work to preserve employee networks and their innovative edge.

***

1. Introduction

In today’s fast-changing economy, the success of companies depends on their ability to innovate—finding new ways to improve products and processes, create efficiencies, and develop new products and services. Where do the best ideas come from? More importantly, what factors inside a company help employees create successful, high-quality innovations?

Social scientists have long argued that an important driver of innovation is social networks – formal and informal relationships between people (in our example, colleagues or clients). Innovation may arise from integrating different experiences, knowledge, and ideas (Jacobs 1969; Weitzman 1998; Obstfeld 2005). Of particular interest are weak ties involving occasional, informal interactions (Granovetter 1973; Perry-Smith 2006; Rajkumar et al 2022), as they may be especially novel sources of these elements. Another key idea from this literature is the potentially important role of those who broker across “structural holes” in the network (Burt 2004; 2005). An employee who has connections to those outside of the core network may have an informational advantage. This may benefit them, but also their network colleagues.

Our recent research gives us new, data-driven insights into the inner workings of employee networks in a large multinational firm—and how those networks affect the quality of innovation. Our findings shed light on how collaboration, network structure, and the shift to remote or hybrid work can shape innovation in the modern workplace.

2. Employee Networks

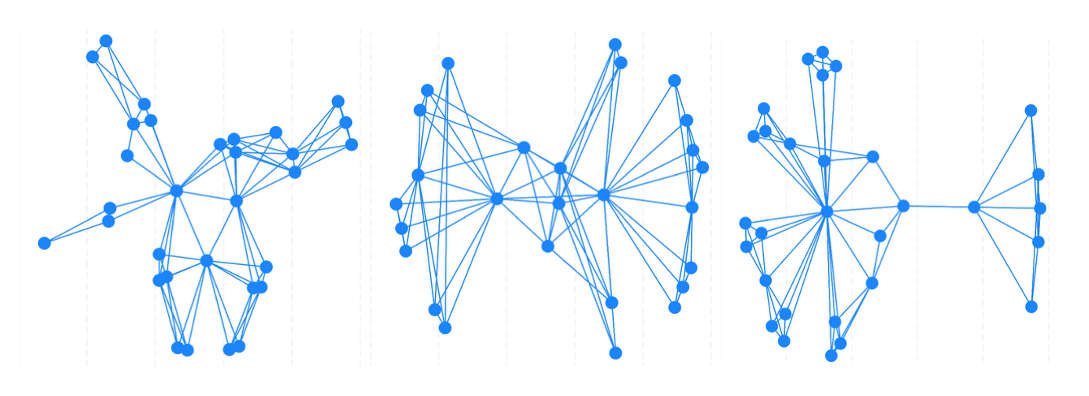

Imagine the collaborative innovation process in a company as a large network of people—some tightly connected teams innovating together, others as lone inventors, and a few acting as bridges between different groups. The way individuals are connected in this network can play a pivotal role in how, and how well, new ideas are generated.

The following figures show three of the networks from our firm data, where each dot represents an employee and each connecting line represents a collaboration.

2.1. What is a Network in the Workplace?

- Nodes: Employees (the people who might innovate)

- Links: Collaborative relationships—who works with whom to develop new ideas

- Network position: Where an employee sits in this network. Are they in the center with many direct collaborators, on the periphery, or acting as a bridge between groups?

Our study is unique because it recreates the network based on all innovations within the firm, which are usually not observable. Most research on networks and innovation relies on publicly available data (such as patents or academic research collaborations, which only show successful innovations, not unsuccessful ones), or on hypothetical within-firm data (such as surveys whose responses are independent from the usual day-to-day at the firm). The innovations in our data are the real ideas that bring the company and its products forward. The data are from a large IT services company (HCL Technologies). We study the proposals that more than 28,000 employees made in the company’s formal idea suggestion system. We observe both ideas that were successful (implemented by the firm) as well as ideas that were rejected. We use those data to construct innovator networks.

2.2. Key Concepts: Degree, Bridging, and Network Size

Networks are highly dimensional objects. The position of a single individual in the network can be described by many different statistics. Our study focuses on three of the most important aspects of an employee’s network position:

- Degree: The number of distinct colleagues an employee collaborates with directly (i.e., how many different co-authors they have)

- Bridge Centrality: A measure of how much an employee connects otherwise separate groups or clusters within the firm—essentially, whether they are a “broker” who bridges “structural holes” between teams (Freeman 1977; Hwang et al 2006)

- Network Size: The total number of people reachable within a given number of steps from an employee. At any given time, there can be multiple disjoint networks within the firm, because there is no one bridging between these distinct networks

2.3. How do we obtain our findings?

We measure innovation quality with two variables, which are highly positively correlated. First, whether the proposed idea was accepted (and implemented) rather than rejected. Second, whether the proposed idea received a high rating (3 or 4 on a scale of 1-4) from clients. The company has strong business incentives to approve only worthwhile ideas, while rejecting poor ones. Senior employees are trained to make these high stakes decisions, so while subjective, we consider these quality measures to be very reliable. In fact, proper assessments of the quality of innovations must be made subjectively.

We aggregated all employee ideas over 6-month time windows and calculated their idea approval rates and whether they received high ratings during that time. In the main statistical analysis, we effectively compare the same employee’s outcomes in a time window when they had a higher degree, to a window when they had a lower degree, in order to determine the effect of degree on innovation quality. Similarly, changes in an employee’s bridge centrality and network size over time are used to estimate the effects of these factors.

3. Major Findings

3.1. Do more collaborators yield better quality ideas?

Employees who collaborated with more colleagues on their innovation proposals tended to have higher-quality ideas. Each additional collaborator increased the probability of a proposal being accepted by on average 2.5 percentage points.

Why? More direct ties bring more knowledge, perspectives, and of course more people to invest time and effort into the development of the idea. The effect is robust even after controlling for other network features, e.g., when holding network size and bridging activity constant.

3.2. Bridging Has Complex Benefits

Acting as a broker—someone who bridges otherwise disconnected groups—revealed effects that are similar to, but more complex than, those found in prior literature:

- Short-term costs: In the current period, being a broker (as measured by high bridge centrality) was associated with lower quality ideas, after accounting for degree. Holding the number of collaborators constant, brokering more is costly for that employee. A possible explanation is increased coordination and communication challenges when connecting employees of different skills and backgrounds.

- Medium-term benefits: Over time, those who bridged more also experienced improved innovation outcomes. Past bridging activity was linked to better future ideas, possibly because of the lasting knowledge and perspectives that brokers gain. A reason might also be the usual advantages of being well connected that one can rely on later.

- Network-wide externality: Importantly, even if bridging did not immediately benefit the broker him- or herself, their colleagues benefited from access to the new knowledge and perspectives that brokers brought in. Having a highly connected broker somewhere in your network increases your own success rate—a clear positive externality.

3.3. Network Size Alone Isn’t Enough

While one might assume that being part of a large network would boost innovation, our findings show that network size itself does not predict higher-quality ideas after accounting for degree and bridging role. It isn’t the number of people you could theoretically reach—it’s how many people you collaborate and connect with directly, as well as which network positions these people occupy, that matters for innovation. It is not the size of the network, but its quality and your position in it.

3.4. Remote and Hybrid Work: The Network Consequences

Due to the Covid-19 lockdowns, all employees at this company suddenly switched from office work (WFO) to work from home (WFH). Later the company switched to hybrid work, where employees were able to work partly from home and partly at the office.

We find that remote work (WFH and hybrid) reduces the number of collaborators, so network degree shrinks. Similarly, bridging activity is also reduced. Networks are smaller in these periods and consist of more disconnected clusters. In another study, we documented that innovation suffered during WFH and hybrid work (Gibbs, Mengel & Siemroth, 2024). Given the evidence discussed above, it seems likely that these network impacts are at least partially to blame for this.

3.5. Why Do Brokers Matter? Their Role as Innovation Catalysts

A particularly important result of our research concerns the role of “brokers.” These are employees who link different groups (e.g., different business units, job functions, or social circles) that might otherwise remain siloed. Brokers bring diversity of thought by connecting different job functions and teams. This can spur new ideas. It can serve as inspiration for new ways to tackle existing problems. Moreover, brokers can serve as a conduit for outside expertise as needed. Indeed, we find that brokers innovate for more clients, and submit ideas in more categories, compared to other employees.

Crucially, their presence doesn’t primarily benefit themselves; it lifts innovation of everyone in their network. There is a short-term pain—brokers bear costs navigating differences between groups—but the collective and longer-term gains are positive. This raises the question of how to manage the tension between individual and collective benefits, and how to foster effective brokering.

4. Practical Lessons for Business, Law, and Policy

4.1. Encourage Collaboration, Not Isolation

Policies and reward systems should motivate employees to reach out and collaborate with a diverse set of colleagues, rather than working in isolation or only with the “usual suspects.” Each additional connection could boost the odds of producing valuable new ideas.

4.2. Support Brokers

Brokers create vital bridges in the company’s social architecture:

- Recognize that brokers may need explicit support or incentives, as their short-term costs are compensated by medium-term collective benefits.

- Consider formal structures (rotations, cross-functional teams, or innovation brokers) to encourage this behavior, rather than leaving it to chance.

4.3. Remote / Hybrid Strategies Need a Network Perspective

The success or failure of remote or hybrid work depends heavily on how well companies can maintain, rebuild, or adapt their networks:

- Regular office days should be carefully coordinated to allow face-to-face interactions between otherwise disconnected groups.

- Invest in digital tools and management strategies that support spontaneous, cross-team connections—not just scheduled meetings.

- Be wary of “hybrid disorganization”—if not well managed, it can cause even more disruption to internal networks than being fully remote.

- Train employees in the benefits of in-person work for their own productivity, innovation, and career success.

5. Concluding Remarks

Innovation doesn’t just depend on the individual genius or even the size of workforces—it hinges critically on how people are connected. Awareness of how the structure of these networks shapes innovation can help companies to design workplaces that foster a creative and innovative culture.

Hybrid and remote work models are here to stay, but can present a challenge for workplace design. Unless organizations actively encourage robust, dynamic, and well-bridged networks, they risk dulling their innovative edge. It’s who you work with that matters for innovation, but also how you connect with other “clusters,” and whether your organization values and supports the brokers who glue the company together. Moreover, in-person interactions are more effective than remote ones (Grözinger et al 2020; Atkin et al 2022; Brucks & Levav 2022).

This is the old challenge: to create workplaces where rich, cross-cutting networks thrive, and where both the connectors and the connected reap the rewards of collective innovation. However, that challenge is more difficult and must be addressed differently with the rise of remote work.

Michael Gibbs,* Friederike Mengel,** and Christoph Siemroth***

* Clinical Professor of Economics at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business

** Professor of Economics at the University of Essex

*** Senior Lecturer (Associate Professor) at the University of Essex

Citation: Michael Gibbs, Friederike Mengel, and Christoph Siemroth, How Employee Networks Drive Innovation, and How Remote Work Alters Both, Network Law Review, Summer 2025.

References

This article summarizes the findings of “Innovator Networks Within the Firm and the Quality of Innovation” by Michael Gibbs, Friederike Mengel, and Christoph Siemroth (2025), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5309987.

- Atkin, D., K. Chen, and A. Popov (2022): “The Returns to Face-to-Face Interactions: Knowledge Spillovers in Silicon Valley,” NBER working paper 30147.

- Brucks, M. and J. Levav (2022): “Virtual communication curbs creative idea generation,” Nature, 605, 108–112.

- Burt, R. (2004): “Structural Holes and Good Ideas,” American Journal of Sociology, 110, 349-399.

- ——— (2005): Brokerage and Closure: An Introduction to Social Capital, Oxford University Press.

- Freeman, L. (1977): “A Set of Measures of Centrality Based on Betweenness,” Sociometry, 35–41.

- Gibbs, M., F. Mengel, and C. Siemroth (2024): “Employee Innovation During Office Work, Work From Home and Hybrid Work,” Nature: Scientific Reports, 14.

- Granovetter, M. (1973): “The Strength of Weak Ties,” American Journal of Sociology, May.

- Grözinger, N., B. Irlenbusch, K. Laske, and M. Schr¨oder (2020): “Innovation and communication media in virtual teams–An experimental study,” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 180, 201–218.

- Hwang, W., Y. Cho, A. Zhang, and M. Ramanathan (2006): “Bridge Centrality: Identifying Bridging Nodes in Scale-Free Networks,” Proceedings of the 12th ACM SIGKDD international conference on Knowledge discovery and data mining, 20–23.

- Jacobs, J. (1969): The Economics of Cities. New York: Random House.

- Obstfeld, D. (2005): “Social Networks, the Tertius Iungens Orientation, and Involvement in Innovation,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 50, 100–130.

- Perry-Smith, J. (2006): “Social yet creative: The role of social relationships in facilitating individual creativity,” Academy of Management Journal, 49.

- Rajkumar, K., G. Saint-Jacques, I. Bojinov, E. Brynjolfsson, and S. Aral (2022): “A causal test of the strength of weak ties,” Science, 377, 1304–1310.

- Weitzman, M. (1998): “Recombinant Growth,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 113, 331-360.

- Yang, L., D. Holtz, S. Jaffe, S. Suri, S. Sinha, J. Weston, C. Joyce, N. Shah, K. Sherman, B. Hecht, and J. Teevan (2022): “The effects of remote work on collaboration among information workers,” Nature: Human Behaviour.