The Network Law Review is pleased to present a special issue entitled “The Law & Technology & Economics of AI.” This issue brings together multiple disciplines around a central question: What kind of governance does AI demand? A workshop with all the contributors took place on May 22–23, 2025, in Hong Kong, hosted by Adrian Kuenzler (HKU Law School), Thibault Schrepel (Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam), and Volker Stocker (Weizenbaum Institute). They also serve as the editors.

**

Abstract

This essay examines how the EU’s Digital Markets Act unintentionally reshapes the foundations of generative AI. By barring gatekeepers from relying on “legitimate interest” as a legal basis for processing personal data, the DMA creates a fragmented two-tier regime: smaller firms retain flexibility, Europe’s largest AI deployers face structural limits on scale. The piece argues that this asymmetry, though rooted in competition concerns, risks undermining innovation, privacy, and Europe’s technological autonomy.

*

When Aesop’s shepherd boy constantly cried “wolf”, the villagers stopped listening. When today’s AI developers and deployers cry “data,” regulators must listen.

Generative AI has taken the market by storm, underpinning most online services catered by dominant and not-so-dominant firms. ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, and others now support everything from search engines to virtual assistants. These technologies rely not just on computation and clever design but on massive amounts of data, much of it scraped from the open web. That data often includes personal data.

This reality has prompted intense legal scrutiny, particularly under data protection frameworks like the GDPR.[2] But there’s a second, quieter layer of regulation now biting at the ankles of AI deployers in the race: the Digital Markets Act (DMA).[3] In its zeal to rein in the market power of a few entrenched players, the DMA has introduced a subtle but far-reaching asymmetry. The legal basis that makes generative AI lawful in most data protection frameworks, such as in the EU, Canada, or China (the data controller’s legitimate interest, as recognised, for instance, under Article 6(1)(f) GDPR), remains off-limits to those economic operators designated as gatekeepers under the DMA. By doing so, the European regulation parcels digital markets by undermining a gatekeeper’s capacity to process personal data in relation to the provision of proprietary AI services, which is not really grounded on concerns around market contestability.

The implications are profound. AI development in Europe may now bifurcate not by type of data or risk of harm, but by whether a given agent is a gatekeeper in terms of the European DMA. In this blog post, I argue that Article 5(2) DMA risks embedding a fragmented legal regime in the very foundations of generative AI.

1. The Promise and Peril of Scale

Generative AI is inherently data hungry due to its own functioning and structure revolving around the tokenisation of strings of words, language, and other types of content. It thrives on learning patterns from oceans of unstructured text, images, audio, and video. This process includes pre-training and fine-tuning on datasets that often include personal data. Despite that AI providers engage in data sharing and extraction agreements, most of the training underlying AI models is scraped from the web. That is, online content is retrieved en masse via automated tools. For instance, scraping takes place by extracting all data from the content uploaded by consumers on their social networks. The inconsequential collection and processing of personal data stemming from web scraping into LLMs has enough potential, by itself, to set data protection and privacy legal standards at odds with the development of any type of generative AI model.

Datasets such as Common Crawl,[4] the largest freely available collection of scraped data, are streamlined by the main AI deployers and developers.[5] OpenAI recognised that its ChatGPT-3 derived 80% of its tokenisation from it.[6] Aside from LLMs, multi-modal generative AI also feeds on scraped data via Large-Scale Artificial Intelligence Open Network (LAION), operating as a database of copyrighted images that some AI developers integrate into their models. On top of that, existing LLMs have been subject to inference attack methods attempting to predict whether particular data belongs within the model’s training data, and the results demonstrate that they were trained on paywalled websites, copyrighted content,[7] and books,[8] all scraped from the web. In a similar vein, paywalled news sites ranked top in the data sources included in Google’s C4 database (used to train Meta’s LLaMA and Google’s LLM T5).[9]

Even though we cannot assert that this or that LLM feeds into scraped data, unless the AI developer discloses it directly (as Meta did recently[10]), fragmentary evidence indicates that we cannot rule out the possibility completely.[11] The cost of scale is, therefore, opacity and lack of transparency, since AI developers are quite reluctant to document and disclose the training sources by which their LLMs have been optimised and fine-tuned. Uncertainty in this field poses broader questions of law, notably in the areas of privacy, data protection, and intellectual property.

Against this background, data protection scholars[12] and authorities[13] have responded in kind by trying to accommodate the AI categories into the broader data protection framework. Based on the premise that AI models do not contain records that can be directly isolated or linked to a particular individual, data protection frameworks rarely fit in nicely with the approximations facing tokenisation as the baseline to any AI model.[14] Due to this reason, the European Data Protection Board tried to bring order to this chaos. When providing clarity on the limitations that data protection and privacy regulation must apply to AI deployers, the EDPB classified AI models into two different groups: those that can be classified as anonymous, because they are not designed to provide personal data related to the training data, and those that cannot. Relating to the former, those that can be classified as anonymous entail that the data protection framework does not touch upon them, to the extent that the processing of anonymous information falls outside of its scope of application. On the contrary, for those cases where AI deployers do not surpass the anonymity test, the GDPR compels data controllers to process personal data based on a legal basis, as set out under Article 6 GDPR. Other data protection frameworks also require such justification of the processing of personal data, such as China or Canada.

For AI development, two legal bases are prominently displayed under the GDPR to justify the processing of personal data. The first legal basis to present itself is that of consent. It entails an affirmative and specific action by the data subject in agreeing to the processing. Given that the datasets and sources fed into the training data of AI models stem from web scraping, the legal basis of consent is completely at odds with such data collection. While consent is the gold standard for most data protection regulations, it is practically impossible to obtain consent at scale from millions of unknown users.

For this reason, most AI deployers demonstrate that they process data on their models based on their legitimate interests. That is the case for OpenAI’s ChatGPT,[15] Meta’s LLaMA,[16] or Alphabet’s Gemini.[17] Those legitimate interests designate the broader benefits the controller or a third party enjoys when engaging in the processing of personal data. In this case, the AI deployer’s capacity to extract value from publicly and readily available information online. The EDPB confirmed that AI developers and deployers can rely on it only if they manage to document whether their actions are limited to what is plausibly necessary to pursue that same interest. In any case, this compromise holds. But now, a new law is crying wolf.

2. Enter the Digital Markets Act

The DMA is the EU’s attempt to capture digital market power by imposing per se obligations and prohibitions upon designated gatekeepers. At this moment in time, the European Commission designated seven economic operators: Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, ByteDance, Booking.com, Meta, and Microsoft. Their designation automatically entails that they must comply with a wide array of obligations imposed due to their scale. One such constraint is Article 5(2) DMA: a prohibition on combinations and cross-uses of personal data across services. Despite the prohibition and the DMA’s pledge to apply without prejudice to other pieces of regulation, such as the GDPR, the regulation exempts the prohibition in those cases where the end users concerned by the processing and combining of personal data consent to the activities. On top of that, Article 5(2) provides an additional caveat to the prohibition: the conduct is also ‘without prejudice’ to the gatekeeper processing personal data relying on the legal basis set out in Article 6(1) GDPR. However, the legislator excludes the undertakings’ capacity to rely on the legal bases of Article 6(1)(b) and (f) GDPR. Those operators designated by the European Commission as subject to the DMA will no longer be able to rely on the legal bases of the data controller’s legitimate interest nor on the necessity of the performance of a contract. Because the DMA applies regardless of purpose, it effectively bars these firms from relying on legitimate interest when combining personal data across services, including for training and fine-tuning their AI models, to the extent that they integrate those into the functionalities captured by the DMA. That carve-out is not subtle. It’s spelled out: Articles 6(1)(b) and 6(1)(f) GDPR—contract necessity and legitimate interest—are off the table.

What remains is consent. But in the AI context, consent is largely unworkable. As a matter of fact, other competition authorities, such as the US FTC, have already voiced out this concern by setting out that the adoption of more permissive data practices (e.g., using data for AI training coming from one’s own service) may be categorised as unfair or deceptive under the consumer protection logic.[18] An AI deployer cannot meaningfully ask for consent from a scraped web forum or legacy news archive. Thus, what’s left?

3. A Multi-Tiered AI Regime Emerges

The result is a two-speed AI regime. Non-gatekeeper companies can process scraped personal data under the legal basis of legitimate interest, assuming they overcome the GDPR’s balancing test. Gatekeepers, by contrast, face a hard block. Unless they silo the personal data they store on their users for each service, they cannot combine or reuse personal data to train or improve their models, abiding by the prohibition under Article 5(2) DMA.

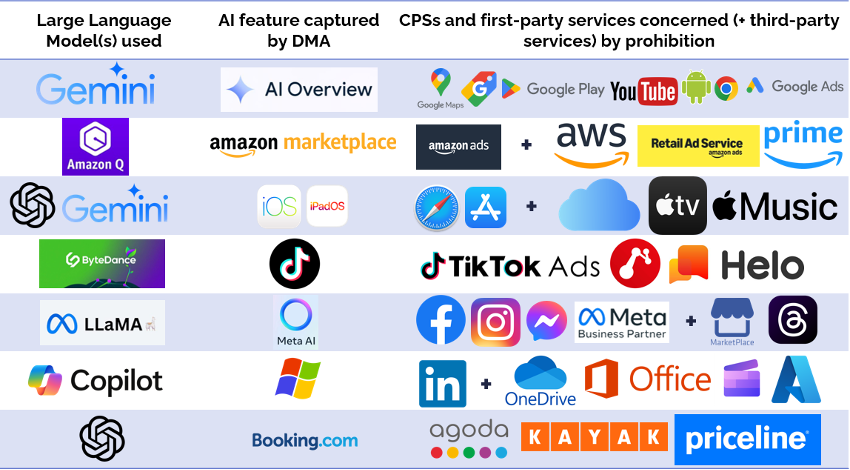

The distinction may seem cosmetic, but it goes to the heart of AI development. Training an LLM like Gemini, LLaMA, or Copilot requires massive and diverse unstructured datasets to start with. If personal data from one service cannot be reused in another, the model’s utility shrinks. If every model must be siloed per service, innovation slows. When one observes the prohibition’s impact on the ground, the consequences turn more dire before one’s eyes:

Figure 1. Examples of services concerned by the prohibition underlying Article 5(2) DMA.

By turning to those examples, one can easily grasp the repercussions of applying Article 5(2) DMA in the context of AI development and deployment. For instance, Google’s launching of its AI Overviews functionality on its Google Search, powered by Gemini 2.0[19] (captured as a core platform service under the DMA), would be directly concerned by the clash between regulations. In this sense, Google would be barred from combining and cross-using personal data derived from user interactions with AI Overview across to the rest of its captured services, such as its online advertising services, Google Chrome, or YouTube. Additionally, the prohibition of data combinations touches upon other Google proprietary services, such as Gmail, Google Photos, and Google Calendar.

Similarly, in principle, the prohibition applies to Meta’s processing of personal data for pre-training and fine-tuning its Meta AI assistant,[20] integrated into the WhatsApp, Facebook, and Instagram experience, when it combines personal data across its services, such as Messenger or its advertising services, as well as its proprietary Marketplace or social network Threads. This entails that Meta’s processing of personal data (as derived from its scraping of content on its social network, which it recently announced) challenges the prohibition entirely.

Furthermore, the prohibition’s consequences are not only felt in how European users’ personal data is processed following the steps of the DMA, but also in other jurisdictions where AI deployment and development actually take place. Let’s take a look at ByteDance’s example. The DMA only designated its social network, TikTok, as a core platform service. Every single feature and functionality embedded in the social network relying on AI faces the data combination prohibition, insofar as they rely on ByteDance’s proprietary foundation model, like Seed-Verifier[21] or its Goku AI video generator.[22] Personal data fed by users to those AI models cannot combine data with other ByteDance services,[23] even if they only remain accessible in the Chinese market, such as social media Helo.

Alternatively, some gatekeeper companies have already adapted to the requirements imposed on AI by Article 5(2) DMA. Microsoft assured in its compliance report that LinkedIn’s AI features rely only on LinkedIn’s data and that it has even excluded personal data from EEA users for its pre-training and fine-tuning processes.[24] Aside from this approach, other gatekeepers have directly opted to outsource the foundation models they operate on. Apple’s iOS (and iPadOS) opted to integrate external models like OpenAI’s GPT-4 and Alphabet’s Gemini.[25] In DMA terms, that means offloading their liability from the prohibition on data combinations. But these are stopgap solutions.

4. Let the Wolf Dance—With a Leash

The Digital Markets Act is not a data protection law. In fact, it declares that it applies ‘without prejudice’ to the GDPR. But it is now shaping how Europe’s largest digital firms can process personal data and, by extension, how they can develop generative AI. As opposed to the US or China,[26] which have prompted the idea that AI providers must be held accountable for the intended users, data sources, and potential societal impacts of the training of their AI, the European Union sets, in black and white, a blanket prohibition on any feasible legal basis for gatekeepers wishing to provide AI services to process personal data for the purposes of training. Although all initiatives point to broader concerns surrounding the legitimacy of training on scraped data for the purpose of innovating via new services or a refurbishing of existing applications, the DMA’s application of Article 5(2) incidentally constitutes the most impactful regulatory response of them all.

By excluding legitimate interest as a valid legal basis for gatekeepers processing personal data across services, the DMA introduces a deep asymmetry into the AI development ecosystem. Not based on risk. Not based on transparency. But based on the structural role a company plays in the market. This stratification effectively fractures the AI development pipeline, allowing some actors to operate with flexibility while others, often those with the capacity to deploy AI at a meaningful scale and present in the AI race on the podium, are hemmed in by conflicting legal duties. This distinction, though grounded in competition concerns, may have unintended consequences for innovation, privacy, and user experience.

At its core, generative AI is about harnessing data at scale to create responsive, dynamic systems. When gatekeepers are forced to isolate datasets, avoid reuse, and silo their AI training practices, the result is not just technical inconvenience, but systemic fragmentation that could undermine competitiveness and undercut Europe’s strategic technological autonomy. Training large models ceases to be a matter of assembling high-quality data and instead becomes an exercise in navigating regulatory walls, duplicating infrastructure, and retraining separate models for each siloed service. Therefore, models will be slower to train, less comprehensive in their outputs and more expensive to develop, bearing in mind the restrictions imposed by the DMA.

Smaller firms and AI providers may briefly benefit from this uneven playing field, but a fragmented regime risks starving the entire European AI ecosystem of competitive dynamics insofar as they depend on shared innovation pipelines and a healthy ecosystem of investment. Thus, the entire European AI landscape risks losing the scale, talent concentration, and cross-sector collaboration required to compete globally. Suppose foundational models cannot be trained on sufficiently representative and diverse data. In that case, Europe will rely more heavily on imports of foreign AI technology, sacrificing both economic competitiveness and regulatory sovereignty. Rather than setting global norms, Europe could find itself importing them, bound by systems whose training practices and design decisions were made under very different legal and ethical assumptions.

There is a wolf in the field. But it is not generative AI itself. The real danger lies in regulatory overreach, mismatched frameworks, and a lack of clarity about what kind of digital ecosystem Europe wants to build. If we are not careful, we may find ourselves crying wolf not at the threat, but at the missed opportunity.

Alba Ribera Martínez [1]

Citation: Alba Ribera Martínez, The Regulation that Cried Wolf: Generative AI Training Data and the Challenge of Lawful Scale, The Law & Technology & Economics of AI (ed. Adrian Kuenzler, Thibault Schrepel & Volker Stocker), Network Law Review, Summer 2025.

References:

- [1] PhD and Lecturer in Competition Law, University Villanueva. ↩︎

- [2] Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation) [2016] OJ L 119/1. ↩︎

- [3] Regulation (EU) 2022/1925 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 September 2022 on contestable and fair markets in the digital sector and amending Directives (EU) 2019/1937 and (EU) 2020/1828 (Digital Markets Act) [2022] OJ L 265/1. ↩︎

- [4] Common Crawl, ‘Common Crawl maintains a free, open repository of web crawl data that can be used by anyone’ (Common Crawl), available at https://commoncrawl.org/. ↩︎

- [5] Stefan Baack, ‘A Critical Analysis of the Largest Source for Generative AI Training Data: Common Crawl’ (2024) FAccT’24: Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability and Transparency, 2199-2208. ↩︎

- [6] Tom B. Brown and others, ‘Language Models are Few-Shot Learners’ (2020), available at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2005.14165. ↩︎

- [7] Sruly Rosenblat, Tim O’Reilly and Ilan Strauss, ‘Beyond Public Access in LLM Pre-Training Data’ (2025) AI Disclosures Project Working Paper Series No. 1, available at https://ssrc-static.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/OpenAI-Training-Violations-OReillyBooks_Sruly-OReilly-Strauss_SSRC_04012025.pdf. ↩︎

- [8] Alex Reisner, ‘The Unbelievable Scale of AI’s Pirated-Books Problem’ (The Atlantic, 20 March 2025), available at https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2025/03/libgen-meta-openai/682093/. ↩︎

- [9] Kevin Schaul, Szu Yu Chen and Nitasha Tiku, ‘Inside the secret list of websites that make AI like ChatGPT sound smart’ The Washington Post (Washington, 21 April 2023). ↩︎

- [10] Meta, ‘Making AI Work Harder for Europeans’ (Meta, 14 April 2025), available at https://about.fb.com/news/2025/04/making-ai-work-harder-for-europeans/. ↩︎

- [11] Shayne Longpre and others, ‘The Data Provenance Initiative: A Large Scale Audit of Dataset Licensing & Attribution in AI’ (2023), available at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2310.16787. ↩︎

- [12] Giovanni Sartor, The impact of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) on artificial intelligence (2020). ↩︎

- [13] The Hamburg Commissioner for Data protection and freedom of information, Discussion Paper: Large Language Models and Personal Data (2024). ↩︎

- [14] European Data Protection Board, Opinion 28/2024 on certain data protection aspects related to the processing of personal data in the context of AI models (2024). ↩︎

- [15] Open AI, ‘Privacy Policy’ (OpenAI, 4 November 2024), available at https://openai.com/es-ES/policies/eu-privacy-policy/. ↩︎

- [16] Meta, ‘How Meta Uses Information for Generative AI Models. What is Generative AI?’ (Meta), available at https://www.facebook.com/privacy/genai. ↩︎

- [17] Google, ‘Gemini Apps Privacy Hub’ (Gemini Apps Help, 24 March 2025), available at https://support.google.com/gemini/answer/13594961?hl=en#legal_basis. ↩︎

- [18] Staff in the Office of Technology, ‘AI Companies: Uphold Your Privacy and Confidentiality Commitments’ (Federal Trade Commission, 9 January 2024), available at https://www.ftc.gov/policy/advocacy-research/tech-at-ftc/2024/01/ai-companies-uphold-your-privacy-confidentiality-commitments. ↩︎

- [19] Robby Stein, ‘Expanding AI Overviews and introducing AI Mode’ (The Keyword, 5 March 2025), available at https://blog.google/products/search/ai-mode-search/. ↩︎

- [20] Meta, ‘Introducing the Meta AI App: A New Way to Access Your AI Assistant’ (Newsroom, 29 April 2025), available at https://about.fb.com/news/2025/04/introducing-meta-ai-app-new-way-access-ai-assistant/. ↩︎

- [21] Carl Franzen, ‘Now it’s TikTok parent ByteDance’s turn for a reasoning AI: enter Seed-Thinking-v1.5!’ (Venture Beat, 11 April 2025), available at https://venturebeat.com/ai/now-its-tiktok-parent-bytedances-turn-for-a-reasoning-ai-enter-seed-thinking-v1-5/. ↩︎

- [22] Liz Hughes, ‘TikTok Parent Company Drops New AI Video Generator’ (AI Business, 12 February 2022), available at https://aibusiness.com/nlp/tiktok-parent-company-drops-new-ai-video-generator. ↩︎

- [23] ByteDance, ‘Our Products’ (ByteDance), available at https://www.bytedance.com/en/products. ↩︎

- [24] Microsoft, Microsoft Compliance Report – Annex 12 – LinkedIn (Online Social Networking Service), (6 March 2025). ↩︎

- [25] Tim Hardwick, ‘Apple Likely to Add Google Gemini and other AI Models to iOS 18’ (MacRumors, 11 June 2024), available at https://www.macrumors.com/2024/06/11/apple-add-more-ai-models-in-future/. ↩︎

- [26] Wang Menglu, ‘Regulation of Algorithmic Decision-Making in China: Development, Problems and Implications’ (2024) Singapore Journal of Legal Studies 1-30. ↩︎