The Network Law Review is pleased to present you with a Dynamic Competition Initiative (“DCI”) symposium. Co-sponsored by UC Berkeley, EUI, and Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam’s ALTI, the DCI seeks to develop and advance innovation-based dynamic competition theories, tools, and policy processes adapted to the nature and pace of innovation in the 21st century. The symposium features guest speakers and panelists from DCI’s first annual conference held in April 2023. This contribution is signed by David J. Teece, the Thomas W. Tusher Professor in Global Business at the University of California’s Haas School of Business (Berkeley).

***

1. Introduction

Competition increases when rivalry incentivizes firms to adopt more “efficient” practices. However, performing a fixed set of activities more efficiently only facilitates “static” competition. Absent significant innovation, efficiency augmenting rivalry does not and cannot deliver significant welfare improvements.

A more powerful force of economic growth and productivity comes from dynamic competition through innovation and entrepreneurial activities. Dynamic competition results in greater customer satisfaction through new and better products and services, priced attractively.

Notwithstanding the rather obvious superiority of dynamic over static competition, competition policy in many countries tends to favor the former over the latter. This would not matter too much if the two forms of competition were strictly additive. But they are not. Pursuing efficiencies and adopting the static paradigm can often suffocate dynamic competition.

The reason for the policy of prioritization of static over dynamic competition is probably that competition economics as a field of study that informs enforcement actions is primarily “deterministic” insofar as it attempts to provide predictability, given specified structural elements and particular competitive contexts. However, static analysis in a dynamic world leads to a false confidence with respect to the understanding of competitive dynamics. Employing the tools of static microeconomics is unsatisfactory when the business environment is riddled with deep uncertainty.

The need for a dynamic competition framework has not suddenly been thrust upon us. But the arrival of “Big Tech” and the ubiquity of digital transformation requires an updating of competition policy frameworks and more urgently so than in previous decades.1The author has been advancing the dynamic competition paradigm for over three decades. See, for example, D. Teece “Capability development” p.192-194 Palgrave Encyclopedia of Strategic Management. Palgrave McMillen, 2018.

2. Key Elements of The Dynamic Competition Framework

2.1. Distinctive elements

Dynamic competition is about new entrants and incumbents engaging in new product and process development in order to create entirely new markets and product categories. In environments characterized by innovation, firms do not just look “sideways” to rivals. They look “forward” and anticipate (and create) latent competition in order to satisfy existing and future user/customer needs, thereby unlocking potential demand and stimulating economic development and growth. Frequent new product introductions, often followed by price declines, are commonplace.2M. Gort & S. Klepper. “Time paths in the diffusion of product innovations” The Economic Journal Sept. 1982 at p. 646.

The dynamic competition paradigm accepts long-run consumer welfare standards (LRCWS) (serving consumer needs more effectively with new and better products, not just lower prices) as the proper welfare standard for competition policy. Of course, competition policy must protect consumers against “anticompetitive” practices and effects in the “meantime” before the “long run” arrives. And it is undeniable that not all markets are self-correcting, at least within a time frame that corresponds to the lawmaker’s discount factor expressed in statutory competition law. That said, the “long run” arrives faster in some markets, and slower in others. When the competitive landscape changes rapidly, competition policies can take a more relaxed perspective on the short-term, and a more vigilant attitude towards the long term. For example, distinct competition policy approaches might be required in the case of the ball bearing industry on the one hand, and of the digital economy on the other.

The dynamic competition paradigm is also quite distinctive in that it recognizes that “value capture,” not just “value creation,” is integral to the competitive process.3While innovation creates value for consumers, rapid innovation and/or infringement of patents and misuse of trade secrets, or even potentially legal reverse engineering may deny the pioneer the ability to capture value. Hence, innovation requires viable mechanisms of value capture by the pioneers to be profitable and hence sustainable. See David J. Teece “Business models, business strategy, & Innovation” Long Range Planning. 2010. Value capture refers to the means by which the innovating firm is able to obtain a share of the value of the improved product or service (i.e., of the value created through innovation), often through technology license fees or more likely other forms of product embodiment.4See David J. Teece “Profiting from Technical Innovation” Research Policy 15:6, December 1986 and David J. Teece “Profiting from Innovation in the Digital Economy” Research Policy, 2018. Value capture should be reasonably and generously tailored to secure the value associated with the improvement that innovation affords and should not be viewed in the main as an anticompetitive practice or a caveat in enforcement policy. Supporting value capture is a central pillar of the dynamic competition paradigm as it encourages investment in R&D and other innovative activities.5The social returns to innovation far exceed private, indicating that incentives for firms are too weak. As a general rule, competition policy should be focused on increasing the returns to innovation, not reducing them. For a brief review of the social returns to innovation literature, see David J. Teece “The ‘Tragedy of the Anticommons’ Fallacy: A Law and Economics Analysis of Patent Thickets and FRAND Licensing” Berkeley Technology Law Journal (2018).

In today’s vernacular, dynamic competition can be thought of as heavyweight competition; static competition is the “lite” and less powerful version. Advocates of impactful competition policy should favor the former, as static competition will only yield marginal welfare improvements without a dynamic counterpart. Adopting such an approach will also enable competition policy to come into alignment with technology and industrial policy. Table 1 summarizes key differences between the static and dynamic competitive paradigms, as explained above:

| STATIC COMPETITION | DYNAMIC COMPETITION | |

| PRIMARY FOCUS | Efficiency; existing markets | Innovation; future markets |

| MANAGEMENT OBSESSION | Competitors | Customers/users |

| FIRM STRATEGY | Compete by offering lower prices | Compete by offering innovative products/services |

| MARKET OUTCOMES | Price reductions for familiar product/services | Innovation and customer solutions through new and better products/services |

| GUIDING PRINCIPLE | Equilibrium | Disequilibrium

|

| COMPETITIVE ARENA | Relevant markets | Ecosystems |

| CONSUMER WELFARE | Minor improvements | With time, major improvements |

| KEY ACTIVITIES | Implementing best practices | Innovation, enterprise formation, learning, capability building, growth, disruption |

| LEVEL OF PROFITS | Mediocre but steady | Strong – with considerable vicissitudes |

| INTELLECTUAL HERITAGE | Neoclassical Economics | Austrian economics; capability, complexity, and evolutionary economics |

| RESOURCE ALLOCATION MECHANISMS | Prices | Prices; managerial asset orchestration according to future demand |

| MANAGERIAL CHALLENGE | Well defined problems; profit maximization goal | Wicked problem solving required in “VUCA” (volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity) environments; profit seeking goal |

| RATIONALITY | Hyperrationality | “Bounded” rationality that recognizes and navigates uncertainty |

| TIME HORIZON | Short run | Longer term, depending on the length of innovation cycles |

| SYSTEM OF INNOVATION | Usually “closed” (within the scope of the parameters of current competition) | Often “open” (beyond the parameters of current competition and looking to the next generation) |

| THEORETICAL STRUCTURE | Competitive equilibrium models; mathematical rigor and (apparent) certainty favored over including variables that reflect the uncertainty of forward-looking conditions (real-world relevance) | Computational economics, evolutionary modelling, statistical analysis, case studies; real-world relevance favored over mathematical rigor and apparent certainty; |

| EVOLUTION OF FIRMS AND MARKETS | Stasis | Constantly transforming/evolving |

| SOURCE OF RENTS (PROFITS) | Hicksian (cost-minimizing with all things remaining equal) | Ricardian (returns to scarcity), Schumpeterian (returns to innovation) / Knightian (reward for uncertainty) |

Table 1. Static v Dynamic Competition Paradigms: Summary

2.2. A new antitrust framework

Dynamic competition requires a forward-looking focus. Like the entrepreneurial manager, antitrust enforcement institutions should not just focus on the past, but concern themselves with potential competition. The ability of nascent competitors or, more likely, other incumbents to expand and compete must be taken seriously as a disciplining factor. As discussed in more detail below, an assessment of capabilities and their redeployability can aid the analysis. Investments that have been made, and technological capabilities that have built that lie beyond the borders of antitrust market definitions but within the broader ecosystem cannot be ignored.

The dynamic competition paradigm draws from business economics as well as complexity economics, innovation economics, and organizational economics. The reason a new paradigm is needed is not just that a policy based on a wrong paradigm will generate decisional errors. A wrong paradigm will bring also about ineffective and damaging policy along with a waste of taxpayers’ money. Consider the Microsoft and IBM cases in the U.S. In hindsight, it seems likely that the decline in market position of both firms had less to do with antitrust intervention by competition authorities6The Microsoft trial was about Microsoft’s extending its monopoly from Windows to browsers, excluding Netscape Navigator, and protecting the operating system from displacement by middleware riding on browsers. Windows retains its operating system leadership on the PC desktop but Internet Explorer (Bing) is largely irrelevant, at least from the consumer search perspective. Google and Apple dominate the browser world owing nothing to the Microsoft antitrust trial. and more with the existence of competition that the enforcement agencies were unwilling to recognize.7See Benedict Evans, How to Lose a Monopoly, Benedict Evans (Jan. 1, 2020), available at https://www.ben-evans.com/benedictevans/2020/01/01/microsoft-monopoly-and-dominance [https://perma.cc/QF84-4NB8].

In some cases, the risk of deploying an inappropriate paradigm is much more severe. In the US, the FTC almost destroyed America’s leading technology provider to the mobile wireless world. Fortunately in FTC v Qualcomm, the lower court decision was overturned by the ninth circuit court of appeals which saved the vigorous dynamic competition which the FTC almost succeeded in crippling. Similarly, the FTC is now spending millions of dollars on a lawsuit against Meta that challenges the lawfulness of a 2012 acquisition of Instagram and a 2014 acquisition of WhatsApp, risking to compromise the key role of M&A market in the funding of innovation.8See Federal Trade Commission v. Qualcomm Inc., No. 19-16122 (9th Cir. 2020). Many State attorneys general have brought a similar suit against Meta that has not been dismissed with prejudice by the D.C. Circuit as untimely, underscoring the backwards-looking focus of their enforcement perspective.

The aim of this short synopsis is to outline the often-subtle foundations that undergird the shortcoming of current competition policy frameworks. The thesis advanced here is that renovating the foundational pillars of competition economics is required so that the broader competitive forces can be properly understood and calibrated. The chair of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (“OECD”) competition committee, Frederic Jenny, seems to agree, noting that in the context of digital platforms and associated M&A activity:

The relationship between competition and innovation is complex and not well understood. … [U]nless competition authorities have a good theory of what makes a digital startup grow and become successful, their assessment of the effects of such mergers will be controversial and they may have to turn to the business economics literature to find clues.9Frederic Jenny Competition Law and Digital Ecosystems: Learning to Walk Before We Run, 30 Indus. and Corp. Change 1143 (2021).

The OECD has also stressed that “the methodology of competition authorities should move from a focus on static competition towards dynamic competition” without, however, lessening their “commitment to the rigor of evidence-based enforcement.”10Global Forum on Competition, Executive Summary: The Impact of Disruptive Innovation on Competition Law Enforcement, OECD Doc. DAF/COMP/GF(2015)15/FINAL, (October 29-30, 2015), https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/GF(2015)15/FINAL/en/pdf [https://perma.cc/7GRP-TRPC] The advice/warnings by Jenny and the OECD are consistent with the thesis of this paper. The dilemmas the agencies are in have not arisen only from the arrival and spread of large digital platforms. They have been festering for decades.

The OECD’s call for the “rigor of evidence-based enforcement” must be answered. Doing so will require assembling evidence of entrepreneurial capabilities and innovation within a relevant competitive ecosystem. Econometric, regression-based analysis of historical (and perhaps outdated) market data provides little insight, and can deflect attention from more important developments and considerations.

Competition authorities may be reluctant to admit, as Jenny suggests, that standard instruments and econometric methodologies that the agencies have relied upon have limited applicability to the digital sector. Jenny recognizes the “fear that the use of conceptual approaches and new instruments for this sector would meet the skepticism of judges who value the stability of jurisprudence.”11Frederic Jenny Competition Law and Digital Ecosystems: Learning to Walk Before We Run, 30 Indus. and Corp. Change note 16, at 1164. The dynamic competition approach addresses the factual economic investigation and the factual economic conclusions to be drawn from investigations.

Antitrust law has already adopted competition economics as its infrastructure. The law must adopt an improved paradigm of competition economics on which to base its factual and, thus legal, findings, as well as its remedial responses.

3. The Role of Capabilities In Competition Economics

The dynamic competition paradigm addresses an omitted variable problem which handicaps competition economics. Explanations for business success and failures in the tech sector and elsewhere are far more complex than the stylized scale, scope, or network effects arguments advanced by static frameworks.

Consider the competitive advantage of Meta, Amazon, Alphabet, Microsoft, and other Big Tech firms. Whatever advantages they have are not built just on current market shares or network effects and scale as many assume. The single most important facet is likely their mastery of new technologies (including, for example, artificial intelligence) and the development of new capabilities and technologies, such as virtual reality.12Big Tech Moves Generative AI To Center Stage, Competition Policy Int’l (March 1, 2023) available at https://www.competitionpolicyinternational.com/big-tech-moves-generative-ai-to-center-stage/; From Apple to Google, Big Tech is Building VR and AR Headsets, The Economist (April 9, 2022) available at https://www.economist.com/business/2022/04/09/from-apple-to-google-big-tech-is-building-vr-and-ar-headsets. The reality is that, as business historian Alfred Chandler noted, the “visible hand” of managers drives innovation and competition.13Alfred Chandler, The Visible Hand, Harvard University Press, 1977. The “visible hand” of management, along with the “invisible hand” of the market, drive the economic system forward. Indeed, the essence of capability theory is that the firm’s ability, by way of the visible hand of management, to allocate non-priced assets/resources to high-value uses, repurposing the asset if necessary, drives firm performance and market outcomes.14See “Technological Innovation and the Theory of the Firm: The Role of Enterprise-level Knowledge, Complementarities, and (Dynamic) Capabilities” in N. Rosenberg and B. Hall (eds.), Handbook of the Economics of Innovation, Amsterdam: Elsevier (2010), 1–15. Competition policy should generally support, and not hinder, such management processes; and competition scholarship needs to invest in understanding the scope and the limits of the visible hand (of management) as well as they understand the invisible hand (of the market).

Admittedly, competition economics has found challenging to incorporate the abstract, qualitative, and often soft teachings of the literature on organizational economics, organizational behavior, and strategic management that management scholars consider important. Yet, in most competition law, the principle is the totality or preponderance of the evidence. Hence, there is no good reason to discount or discard a source of empirical knowledge on the ground that it is not expressible in hard, formal, and quantitative terms.

3.1 Incentives, Capabilities and Supply Side Implications

The understanding of managerial motives and behavior can no longer be limited (as is the case with static frameworks) to “incentives,” pricing and output decisions, and agency and transaction cost issues. While each is important, alone and even together, they are a insufficient guides to the understanding of business behavior.

Indeed, incentives explain far less than economists tend to believe. They are too frequently appealed to by economists as the talisman. “Incentives” alone did not bring us the iPhone—it was software and design capabilities that Apple had that incumbents didn’t have, coupled with the drive of Steve Jobs and others around him to “make a small dent in the universe.” Incentives alone do not explain the birth and growth of Tesla or SpaceX. Moreover, without a deeper understanding of managerial options and organizational constraints, appeal to incentives is wholly inadequate as an explanatory variable. A narrow focus on incentives often deflects attention from other equally important structural, behavioral, and capability considerations.

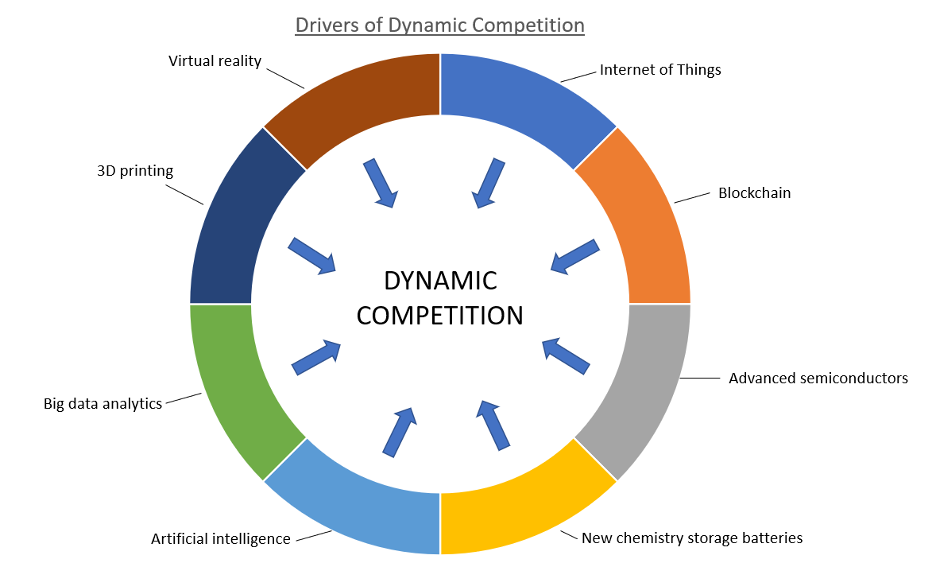

Figure 1. Selected Technologies Shaping/Driving Dynamic Competition 2023

Moreover, innovation drives competition as assuredly as competition drives innovation. Because of the endogeneity issues surrounding the innovation-competition nexus, it is critically important to delve deeper to discover the missing (omitted) variables in the innovation-competition nexus. The leading candidate is firm-level capabilities. Fortunately, there is an exploding body of research on this topic (outside of mainstream economics) which can inform competition economics.15See David J. Teece “Explicating Dynamic Capabilities: The Nature and Microfoundations of (Sustainable) Enterprise Performance” Strategic Management Journal 28:13 (December 2007), 1319– 1350.; “Towards a Capability Theory of (Innovating) Firms: Implications for Management & Policy” Cambridge Journal of Economics (2017).; Dynamic Capabilities: Understanding Strategic Change in Organizations, Constance E. Helfat, Sydney Finkelstein, Will Mitchell, Margaret A. Peteraf, Harbir Singh, David J. Teece, and Sidney G. Winter, Oxford: Blackwell (2007). It’s time for this research to be improved and harnessed.

Capabilities can be “ordinary,” “superordinary, ”or “dynamic.” Ordinary capabilities can support “best practices” and efficiency;16Super ordinary are signature practices somewhat beyond “best practices.” dynamic capabilities support innovation and the reallocation of resources to higher valued investment. The latter are the most critical to dynamic competition.

Until competition economics can develop frameworks and models that are informed by capabilities theory, it will not accurately appreciate the nature of a company’s market power or diagnose the source of any such power. Nor will more complex questions be well addressed, such as the likely impact on competition of a particular business model or merger, especially acquisitions of “nascent” competitors.

Strategic management scholars commonly recognize that the assessment of competition and the strength of rivalry inevitability involve the notion of capability or competitive “distance,”17David J. Teece, A Capability Theory of the Firm: An Economics and (Strategic) Management Perspective, 53 New Zealand Economic Papers 1, 11-12 (2019); David J. Teece “The Foundations of Enterprise Performance: Dynamic and Ordinary Capabilities in an (Economic) Theory of Firms” Academy of Management Perspectives 8(4) (2014), 328–352. i.e., how hard is it to build or modify the capabilities of the business enterprise to expand or shift the company’s competitive domain.18Traditional textbook microeconomics assumes that isoquants are smooth and twice differentiable and that firms can move around with respect to (public) technologies employed at zero cost and with alacrity. For a sense of what a neo-Schumpeterian theory of the firm would look like, see S. Winter “Toward a neo-Schumpeterian theory of the firm” Industrial and Corporate Change. Feb. 2006 and D. Teece “Technological Innovation and the Theory of the Firm: The Role of Enterprise-level Knowledge, Complementarities, and (Dynamic) Capabilities” in N. Rosenberg and B. Hall (eds.), Handbook of the Economics of Innovation, Amsterdam: Elsevier (2010) The assessment of capability distance is also central to any assessment of competition and potential competition, and supply elasticities, within and across markets.19See David J. Teece, “The Dynamic Competition Paradigm: Implications and Illustrations“ Columbia Business Law Review, forthcoming 2023

Despite its obvious importance to the understanding of the supply side of a market and to supply elasticity, the assessment of capabilities, capability distance (and mobility barriers) is rarely attempted in any systematic or primary way by antitrust enforcers or competition economists. Accordingly, the assessment of firm-level factors that explain the reasons for business success is usually incomplete. This ignorance continues to fuel what Nobel laureate Oliver Williamson referred to as the “inhospitality tradition” towards business, and now towards Big Tech. Whatever isn’t well understood is too frequently attributed by economists to monopoly.20See R. Coase “Industrial Organization: Proposal for Research” Economic research: retrospect and prospect, volume 3, policy issues and research opportunities in industrial organization. As Coase remarked poignantly:

If an economist finds something—a business practice of one sort or another—that he does not understand, he looks for a monopoly explanation. And as in this field we are very ignorant, the number of ununderstandable practices tends to be very large, and the reliance on a monopoly explanation frequent.

The problem to which Coase refers is rife when it comes to the issue of capabilities and capability development. A deeper understanding of capabilities and how they are developed and maintained can provide powerful insights into firm behavior and competitive outcome.21See David J. Teece “Capability development” p.192-194 Palgrave Encyclopedia of Strategic Management. Palgrave McMillen, 2018. A failure to consider the role of capabilities in competitive assessments means that economists and competition agencies have created a large “omitted variables” problem. The understanding of the origins of alleged monopolies and monopoly profits cannot begin, let alone be complete, without a systematic understanding of important factors such as capabilities, business models, and systems issues. Such considerations are not yet the stock in trade of competition economists, and this needs to change. Furthermore, capability development often requires M&A. This may implicate “nascent competitors,” as described in a later section.22This is discussed in Section 6 below.

Application of the dynamic competition framework will require a more comprehensive assessment of supply-side factors, especially entry barriers, and incumbency. It is on the supply side that economists encounter their greatest challenges or “ignorance,” if one is to use Coase’s descriptor. Rather than adopting the static view and seeing incumbency as a shield, the dynamic competition paradigm often exposes incumbency as a liability insofar as the incumbent becomes fixated on protecting its existing ordinary “known territory” and is thereby blinded to the nascent and peripheral threats that are just over the horizon.

3.2 Administrability

As noted, a wider lens is needed to recognize a broader range of competitive factors, including the organizational and managerial capabilities of the incumbents and the so-called “fringe.” Exogenous developments in science and technology must also be considered when assessing whether incumbency implies durable market power. It also requires an understanding of new and potential entrants and their likely competitive viability, both of which are primary subjects of study in the dynamic competition paradigm.

The dynamic competition framework also invites an overhaul of the conventional approach to market definition, market power, supply responses, entry, and procompetitive justifications. The framework substantially revises assessments of the supply side and broadens consideration on the demand side.

The question arises as to how one should assess dynamic issues, as administrability and predictability matter in developing legal standards.23It is of course important to recognize that administrability matters. As Tim Muris has noted, “the suitability of an economic hypothesis for shaping antitrust doctrine should be measured by whether the hypothesis lends itself to the development of standards that courts and enforcement agencies can administer effectively” Remarks before George Mason University Law Review. Jan. 15 2003. Fortunately, the dynamic competition offers an entirely workable standard insofar as it calls for a careful factual assessment of competitive realities and a judgment about the likelihood of future competitive harm, which is the same analysis that enforcement agencies undertake today. The difference between the current static approach and the dynamic approach is not ease of application or predictability but the lens through which competitive facts are assessed. The dynamic approach is more attuned to emerging competitive threats and less inclined to reject them as “speculative,” “untimely,” or “insufficient.”24Guidelines on the assessment of horizontal mergers under the Council Regulation on the control of concentrations between undertakings (OJ C 31, 5.2.2004, pp. 5-18).

To be clear, strong dynamic capabilities are not a predictor of market power. It is a competing explanation for market success to be evaluated alongside scale, scope, network effects, and other textbook “go to” explanations. In dynamic contexts, mergers are more often than not animated by goals other than efficiency or market power. They may be driven by the desire to enhance capabilities, which in turn strengthens a firm’s dynamic capabilities, which in turn strengthens dynamic competition.

Static models of competition implicitly venerate staid, cost-cutting, routinized competitive strategies, mindsets, and mergers. The dynamic approach embraces different thinking, and recognizes the importance (to long-term viability and financial performance of the business enterprise) of the successful navigation of uncertainty, and inventions that fuel growth and employment. It’s less friendly to staid static efficiency mergers that do nothing to promote dynamic competition.

But how are regulators supposed to make informed policy judgments about future competition? The answer lies in part in the broad investigative power of regulators (which exceeds those of management… certainly with respect to the internal deliberations of competitors). The burden that regulators must meet is to show that a given proposed transaction will probably substantially lessen competition. Regulators can and should obtain information from the parties to a merger and ecosystem players to assess the state of research, development, and product development to gain as comprehensive a view as possible of prospective innovation and supply-side dynamics.

4. Mergers And Supply Side Analyses

The dynamic competition framework (including the assessment of technological, organizational, and managerial capabilities) is sufficiently mature to inform merger analysis. The agencies can start here. The traditional focus on shares in relevant markets as a way to assess the likelihood of a substantial lessening of competition is highly problematic. Without including as a central element a capabilities and innovation assessment, existing competition paradigms cannot remain the bedrock for competitive assessments.25This may already be the case for merger analysis. Even if the approach today is less structural than in the past, there are calls for a return to more structural assessments (e.g., Shapiro) perhaps this is the opportunity to bring in new notions of structure that embrace capabilities as well as market shares.

Judges must be trained to look first to innovation and capabilities and insist that any showing that a merger will probably substantially lessen competition has accounted for, with a preponderance of the evidence, the likely effect of innovation. Innovation cannot be an affirmative defense whose burden is laid at the doorstep of the defendant. Demonstrating a likely anticompetitive effect notwithstanding innovation in and around the relevant competitive venue must be the burden of the plaintiff if innovation is going to gain necessary legal significance.

The traditional approach of assessing competition by looking for demand-side substitutes is thus inadequate. Although the merger guidelines recognize that, if a “rapid supply response” is easy, market concentration is not a good measure of market power, little guidance is provided as to when such a rapid supply response should be acknowledged.26See Guidelines on the assessment of horizontal mergers under the Council Regulation on the control of concentrations between undertakings (OJ C 31, 5.2.2004, pp. 5-18). A supply response that is not “rapid” and requires nontrivial investment, as does most innovative responses, is treated as “entry,” for which the criteria are severe and become the burden of the merging parties to meet. Unlike the enforcement agency, the merging parties do not have the power to subpoena third parties for documents during the merger review period.

The guidelines are thus “stacked against” crediting the viability of supply responses and otherwise provide little basis for considering innovation as a justification for the merger. There is thus too strong a tendency to dismiss potential entry. This is erroneous, especially given how swift entry can be in the digital economy even though that entry rarely announces itself in advance of its occurrence.

Looked at from a distance, it is rather difficult to comprehend the focus, sometimes even infatuation, with demand-side considerations in defining markets and identifying market participants, assessing market power, and determining the effects of proposed mergers. In the context of innovation and the real-world dynamics of competition, the supply side has far more relevance. The demand side is almost immaterial when old markets are being transformed. Just as the entrepreneur has been squeezed out of the theory of the firm,27See William Baumol “Entrepreneurship in Economic Theory” American Economic Review, 58, 64-71. so has the supply side been squeezed out, or at least marginalized, in competition economics.

Let us consider an example that illustrates how the focus on the supply side could work in practice and what the implications would be. First, Adobe’s desire (which as of this writing remains subject to regulatory scrutiny and approval)28At the time of writing, the case review is still open and the UK CMA has until 30 June 2023 to give a decision on Phase 1 and announce if there will be a Phase 2 inquiry. to purchase Figma would appear to fall into the category of acquiring technological assets that would help facilitate capability enhancement and corporate renewal.29Figma is a web-based collaborative design platform. Adobe agreed to acquire Figma for approximately $20 billion in 2022. The acquisition is being reviewed by regulators around the world and the DOJ is reportedly preparing to file a lawsuit to block the acquisition. See, Adobe Press Release, Adobe to Acquire Figma (Sep. 15, 2022), available at https://news.adobe.com/news/news-details/2022/Adobe-to-Acquire-Figma/default.aspx; Leah Nylen, Anna Edgerton and Brody Ford, DOJ Preps Antitrust Suit to Block Adobe’s $20 Billion Figma Deal, Bloomberg (Feb. 23, 2023) available at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-02-23/doj-preparing-suit-to-block-adobe-s-20-billion-deal-for-figma. The merger was positioned by Adobe as the centerpiece of a necessary transformation that it seeks to effectuate.30See Brody Ford, Adobe’s Plan for Transformation Hinges on DOJ Nod on Figma Deal, Bloomberg Law (Nov 7, 2022), https://news.bloomberglaw.com/antitrust/adobes-plan-for-transformation-hinges-on-doj-nod-on-figma-deal [https://perma.cc/C94D-99AY]. Adobe apparently rejected comparisons to the FTC’s description of Facebook’s acquisition of Instagram, noting that Figma’s design tools do not compete with Adobe’s most important products.31Id.

Figma maintains that the acquisition will give it the resources needed to accelerate development.32Id. If first impressions from an external observer are correct, Figma’s capabilities will help Adobe migrate to a next-generation suite of collaborative products. This will enable it to stay relevant, thereby providing stronger competition to Microsoft and possibly Oracle and Salesforce.

A focus on the supply side could lead to legitimate concerns when a nascent competitor, capable of developing into a mature and able competitor is acquired. However, for such concerns to warrant a regulatory intervention, a nascent competitor would have to be credible with respect to delivering competency-destroying innovation to a putative incumbent acquirer that possesses monopoly power.33Petit, Nicolas, and David Teece. “Capabilities Checklist for Mergers with Nascent Competitors.” Journal of European Competition Law & Practice (2023). At least the following conditions would need to be met: (1) The acquiring firm has monopoly power; (2) The nascent firm’s technology has passed proof of concept (i.e., the technology works); (3) The nascent firm has a proven business model to monetize the technology; (4) The nascent firm has an existing entrepreneurial leadership and strong ordinary, super ordinary, and dynamic capabilities to carry it forward for at least 5-10 years or has a credible succession plan in place; (5) The nascent firm’s technology will be disruptive to core revenue streams of the acquiring firm; (6) The technology of the nascent firm is not competency-enhancing (complementary) to the acquiring firm. Rather, it’s primarily competency-destroying and, hence, threatening; (7) There are no other nascent competitors similarly situated. The above criteria require the assessment of capabilities in a way that is rarely attempted in merger analysis. However, they are administrable criterion and no doubt can be refined further.

5. Conclusions

It is now time for all of us to enforce the dynamic competition framework. This means developing competition policy and crafting enforcement actions informed by a general principle: innovation drives competition at least as much as competition drives innovation. Prioritizing dynamic (non-static) competition can bring monumental benefits to consumers, certainly in the long run, if not also in the short run. Jenny, again, has encapsulated what’s at stake when he declared:

“an exigent intellectual effort is the only way to ensure that competition authorities will avoid the risks of inadvertently giving in to the political pressure of economic populism or ideology or issuing misguided decisions which may be ineffective or, even worse, restrict competition or innovation.”34Frederic Jenny “What role does competition policy play in ensuring that dynamic competition in digital markets works best for consumers? And what are some lessons the APAC region can take away from the EU/US experiences?” Competition Policy International (2022).

Fortunately, a large body of research in evolutionary economics, the behavioral theory of the firm, technology management, information science, entrepreneurship, complexity economics, and strategic management is available to assist the required intellectual effort. That research can be used to hasten the transition toward a more enlightened approach to competition analysis that better approximates real-world conditions and minimizes the negative consequences of (static) antitrust analysis.

David Teece35Professor of the graduate school, UC Berkeley and executive chairman, the Berkeley Research Group. I wish to thank Nicolas Petit, Henry Kahwaty, Bo Heiden, Bill Rooney, Chris Pleatsikas, Thibault Schrepel, Greg Sidak, and many others for their very helpful insights and comments over many years. This paper is a precursor for forthcoming articles by this author in the Columbia Business Law Review and in the Antitrust Law Journal.

| Citation: David J. Teece, “Dynamic Competition, Organizational Capabilities, and M&A: A Short Synopsis”, Network Law Review, Summer 2023. |